The unfold

According to Deleuze, ‘To develop is to unfold’ (1986, p. 9). Within my ‘mental landscape’, the informal waves merge through diffractive thinking[1] as the visual folds, unfolds, and folds again before morphing within the virtual space of my mind. The informal, for Andrew Benjamin (The Appearance of Modern Architecture, 2004) is the matter or material before it is formed. For Deleuze, ‘the informal is not the negation of form; it posits form as folded, as existing only as “mental landscape,” in the soul or the mind,’ (1991, p. 243). Creating may be considered as the process of folding material into different thoughts[2]. Leibniz states, ‘this action would consist in certain vibrations or oscillations… not only do we receive images and traces in the brain, but we form new ones from them when we bring ‘complex ideas’ to mind’ (1996, pp. 145-146).

According to Deleuze, this unfolding process is not contrary to the folding nor its erasure. It is a continuation, extension, and condition of its manifestation. ‘When the fold ceases to be represented and becomes a “method”, an operation, an act, the unfold becomes the result of the act’ (Deleuze, 1991, p. 243). The act becomes the continuous process of folding and unfolding, as Leibnizian abstraction unfolds within the literal folds of the human brain (ibid., p. 231)[3].

Kinloch Hourn (2022) – Lynda Beckett

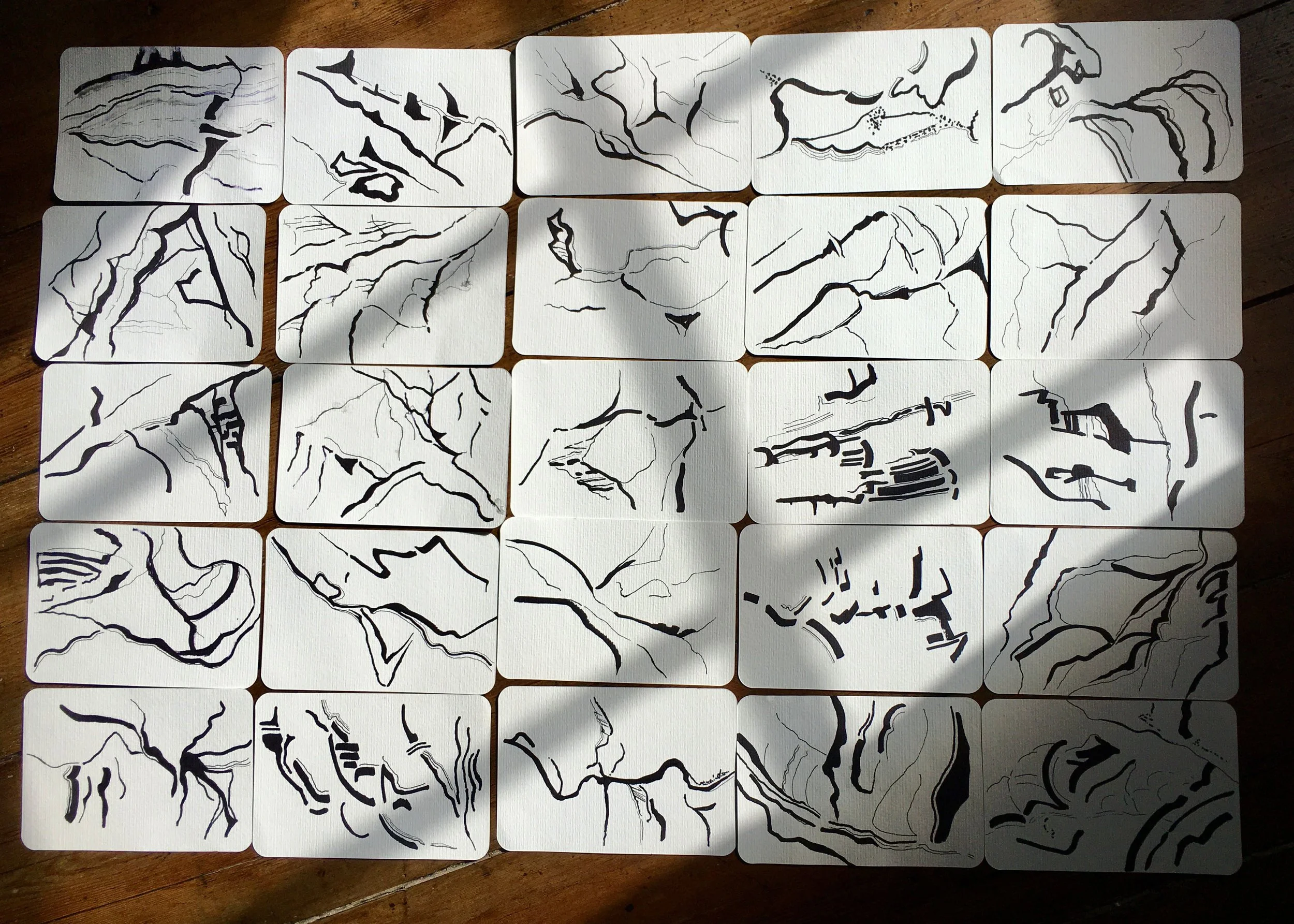

As I write, my thoughts unfold and diffract within my mental landscape. Drifting from my studio, I return to an isolated part of western Scotland. Once off the main road, it takes 45 minutes of twisting and turning down a bumpy single track to arrive at Kinloch Hourn. On a clear day, you can see the Isle of Skye from the head of the loch. Pivot south, and the landscape appears marked by natural folds and the occasional manmade scar, a road or path. Curious about the tracks and traces (Ingold, 2016, pp. 42–46)[4], having followed them for several days, I put pen to paper. The process was impulsive. I traced the tracks, making staccato-like movements with the pen, in response to the rhythm of the landscape, while paying little attention to the paper.

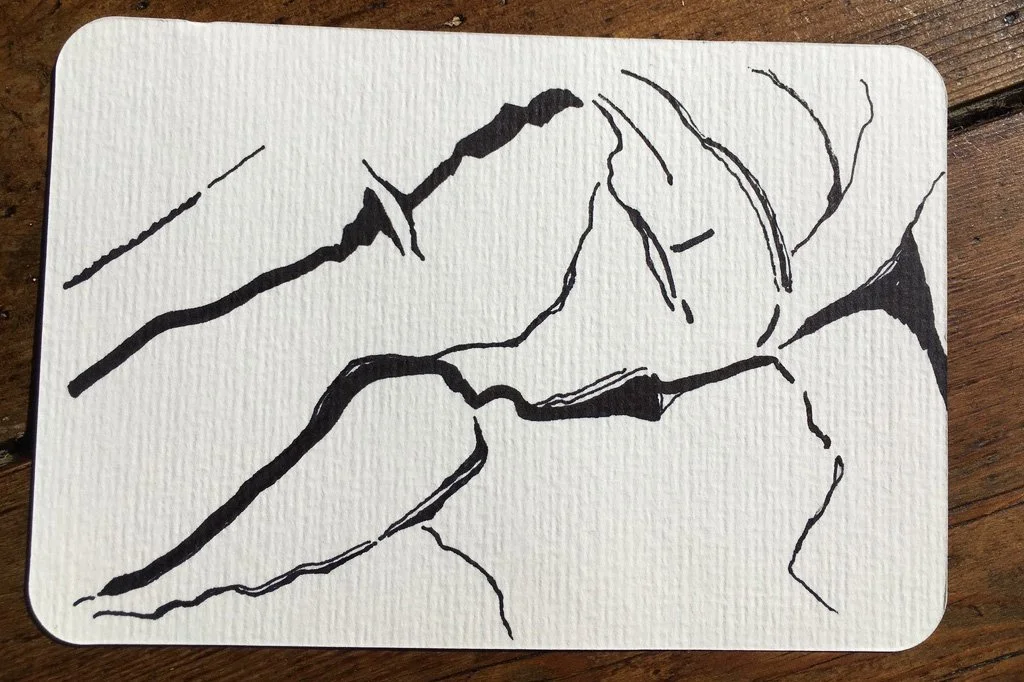

Tracks and Traces (no:9) (2022) – Lynda Beckett

Back in Yorkshire, without the original orientation of the drawings, a new cartography developed from a seemingly chaotic sequence of similar but different forms. New lines emerged and flowed across the artwork. The drawings found their rhythm. A rhizomatic pattern developed. The geographical tracks and traces transformed and created a graphic score without bars or staves. This method of mark-making is important to my practice. A new language forms, unfolds, one that refuses to fulfil the demands of any dominant codified structure.

Series of Tracks and Traces (2022) – Lynda Beckett

[1] Diffraction for Haraway ‘is a mapping of interference, not of replication, reflection or reproduction' (Grossberg et al., 1992, p. 300). See, Diffraction & Reading Diffractively, Geerts, E. and van der Tuin, I. (2016) for their interpretation of diffraction.

[2] Perhaps this ‘mental landscape’ is a depository of thoughts, images and sounds. A place where the aural and visual merge and, when recalled, form a different image or sequence of images in the form of memory.

[3] The body as flexible and fractal, is borrowed from Leibniz (1996, pp. 144–145).

[4] The anthropologist Tim Ingold defines the threads and traces within our environment. He suggests threads are filaments and traces are ‘any enduring mark left in or on a solid surface by continuous movement’ (2016, pp. 42-44)