Textures

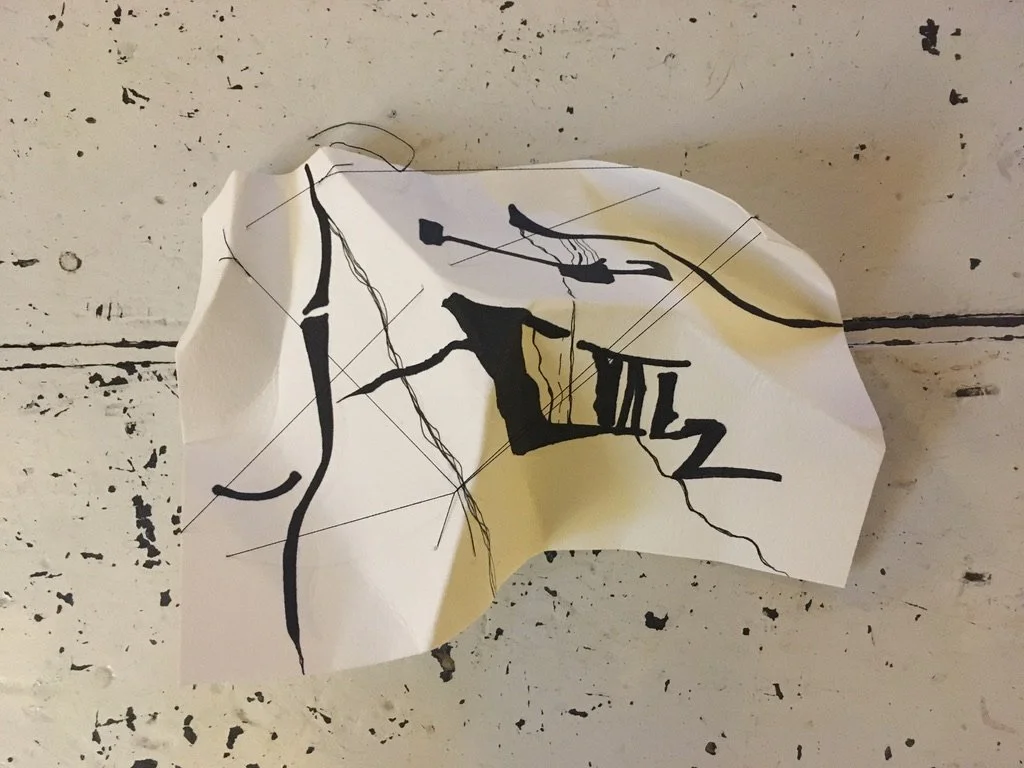

31/10/2012-21 (2021) – Lynda Beckett

I have considered, ‘the fold’, ‘the interior and the exterior’, ‘the high and the low’, and ‘the unfold’. There are two further traits of the fold to contemplate: ‘textures’ and ‘the paradigm’ (Deleuze, 2006, pp. 41–42). Within my practice textures are often translucent and porous layers that allow sensual matter to pass through. In the film 31/10/2012-21 (2021)[1] a mass of digital layers touch upon complex folding textures, as both the audio and video entangle. This piece has a roughness of texture, as a reading of Virginia Woolf’s short story The String Quartet (2019) crashes into the shipping forecast, and light patterns and images diffract over a German reading of Franz Kafka’s The Cares of a Family Man (2003), while I explain the concept of Odradek to my therapist, and short bursts of birdsong punctuate this virtual landscape. Intensity and chaos reign. Yet when making the piece, the different strands of video and audio seemed to find their natural folds as they cut together. Perhaps, as Deleuze suggests, it is at its limit that texture becomes most evident as folds evolve and different planes/patterns emerge (2006, p. 41). These patterns seem to hold the sensual within the threads of 31/10/2012-21 (2021). This is an important consideration because I think the new will be discovered within my practice at the point of chaos.

The Paradigm

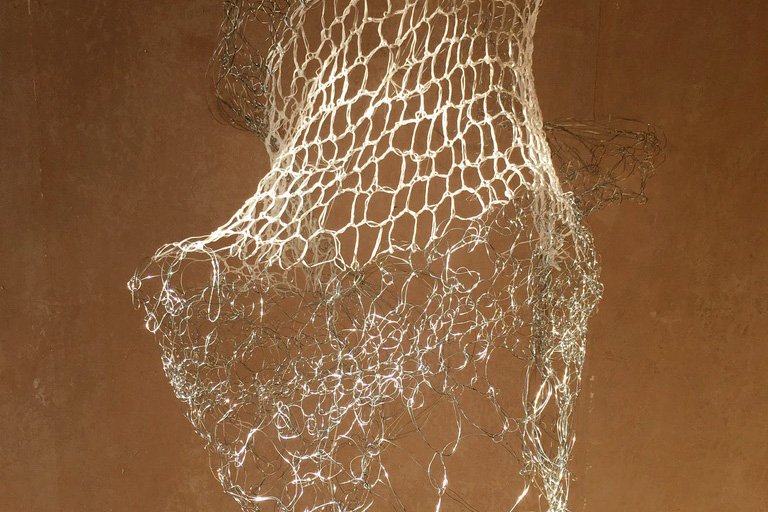

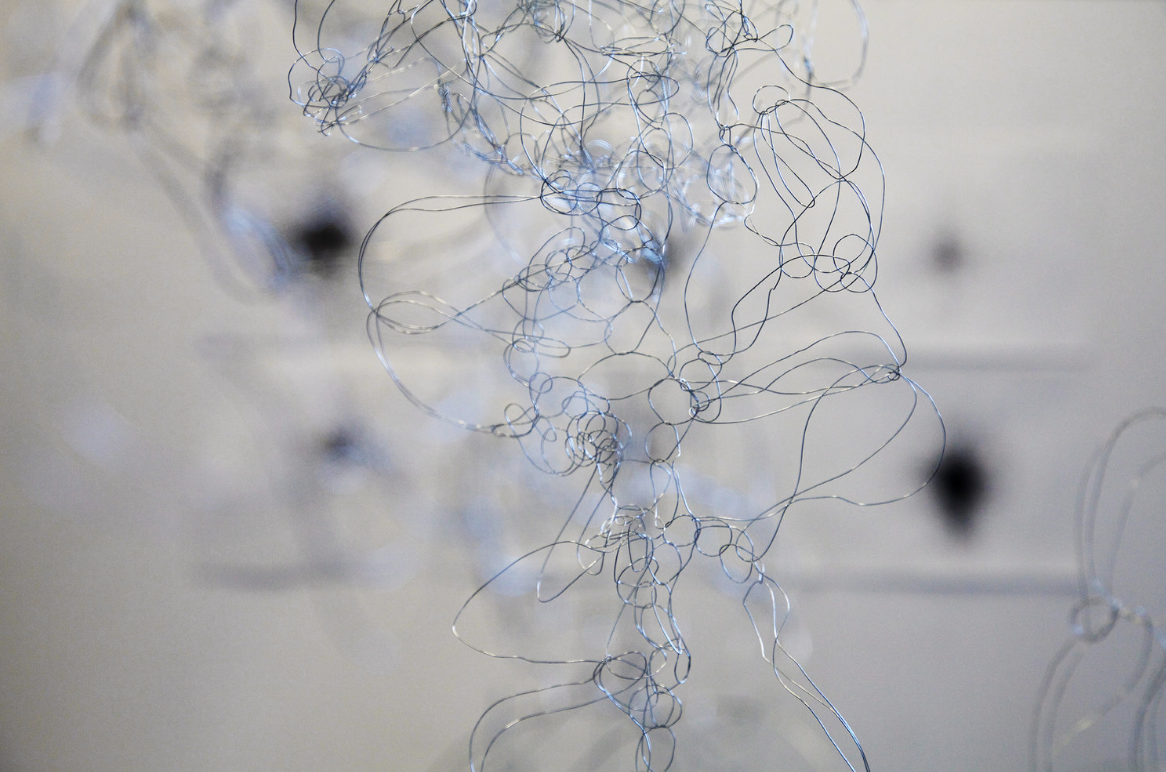

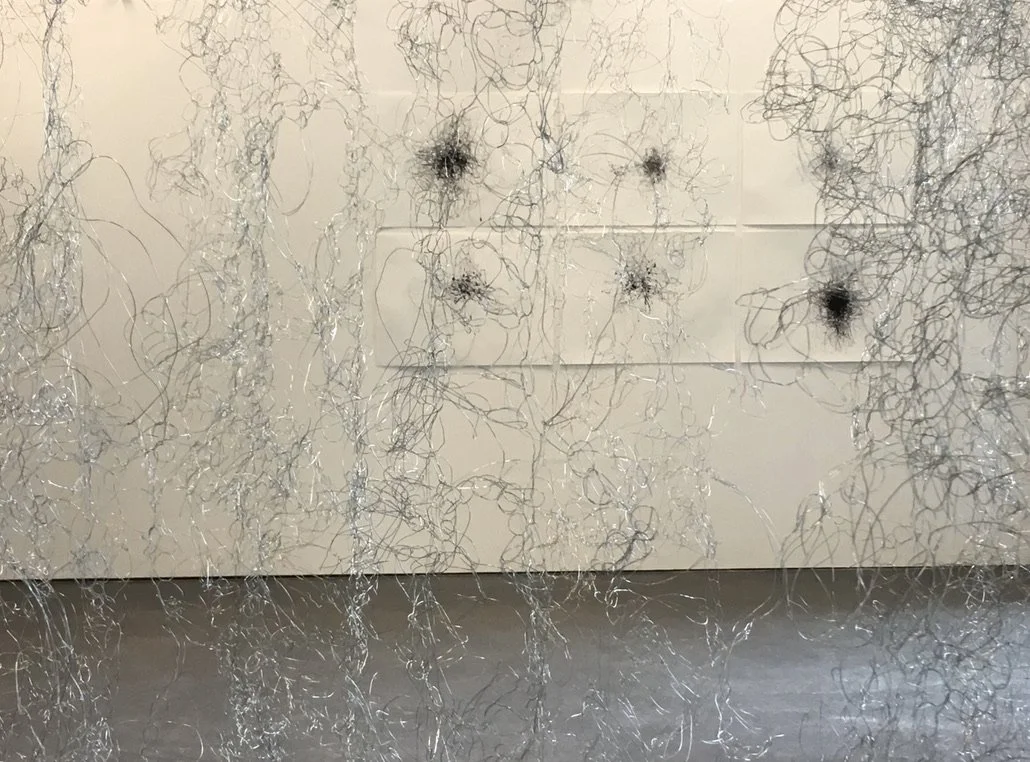

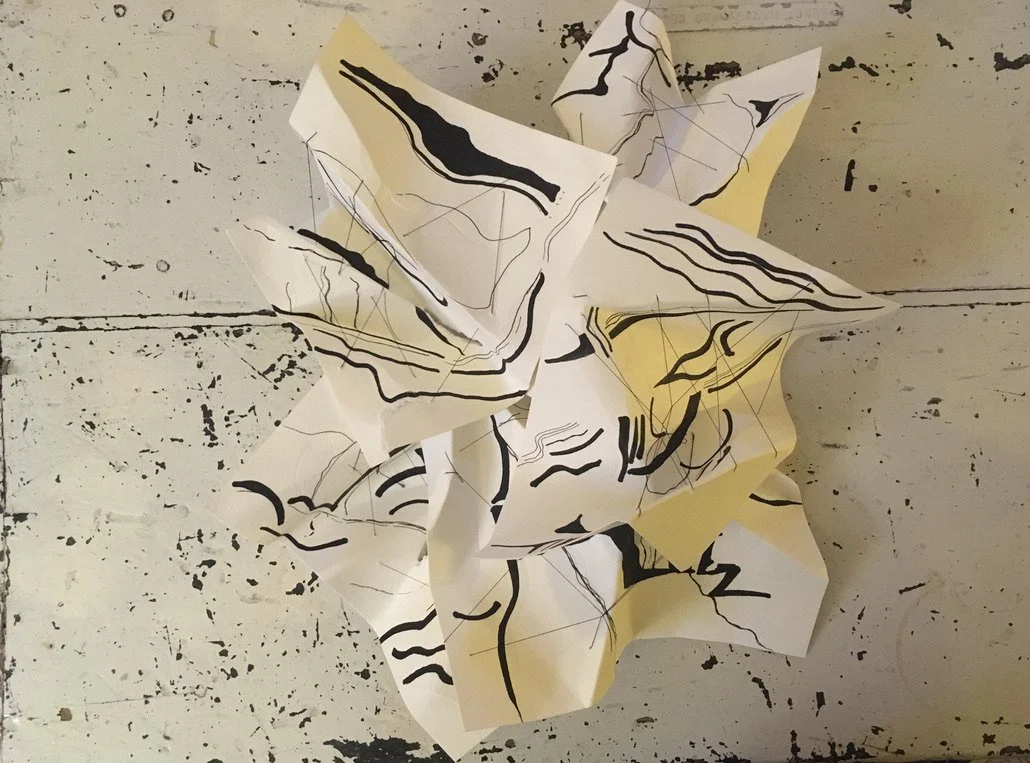

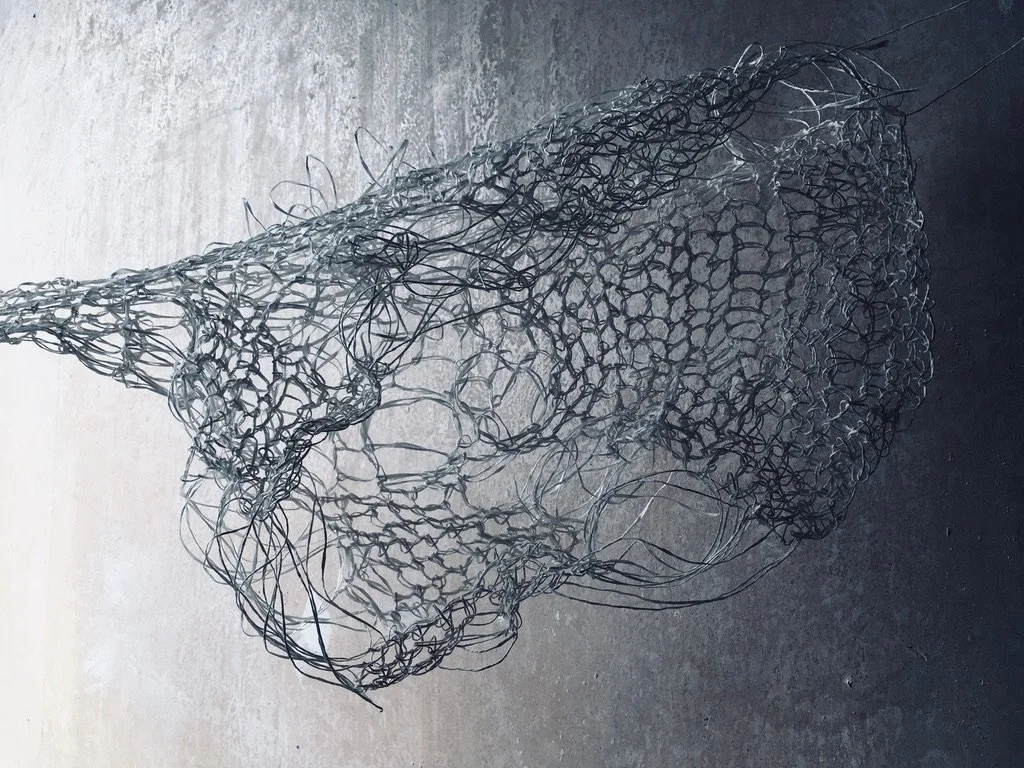

SKIN I (2020) – Lynda Beckett. https://www.lyndabeckett.org/#/skin-i/

The remaining trait is the paradigm, ‘the search for a model of the fold (which) goes directly through the choice of a material’[2] (Deleuze, 2006, p. 42). SKIN I (2020) is an unstructured, chaotic, irregular, and amorphic mass of knots. Within the form, the choice of physical material was immaterial. A repetitive configuration of fractal cell-like shapes gives the sculpture form. The surface is a patterning of threads, a framework that gives texture to the form, which in turn covers the informal, that which is prior to form. Perhaps the folds enable the thinking to materialise as form. SKIN I evokes memories of transparent skin on the verge of death.

The physical material, the knotwork, holds nothing. Yet raw data, as the socio-political, conceptual, geographical, and the sensual, seep out from within the form. The once human framework morphs into a knotwork of folds within a fold.

From another perspective, short videos became portals into virtual worlds, via the sensual, within my knotwork. This framework for making and thought developed from the theoretical work of Thomas Nail. He describes knotting as a method to entangle two or more fields to form knotworks (2019, pp. 147–148).

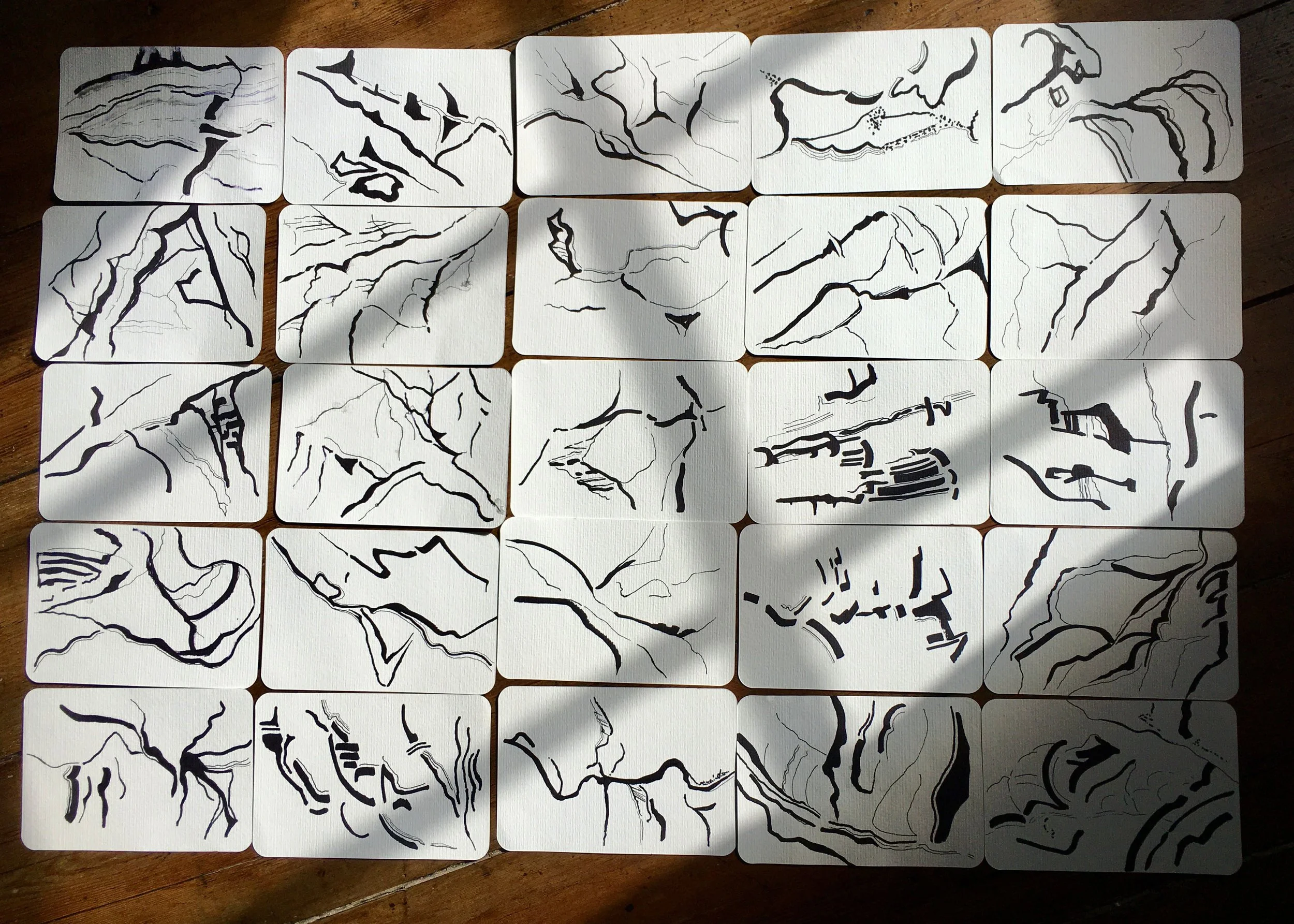

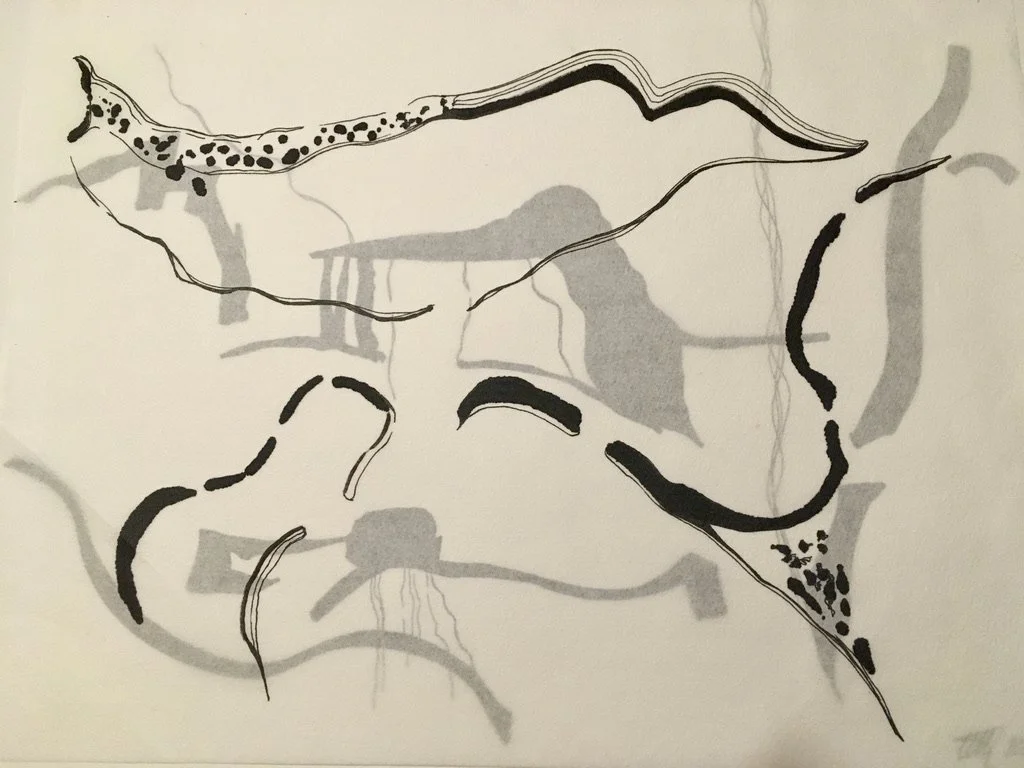

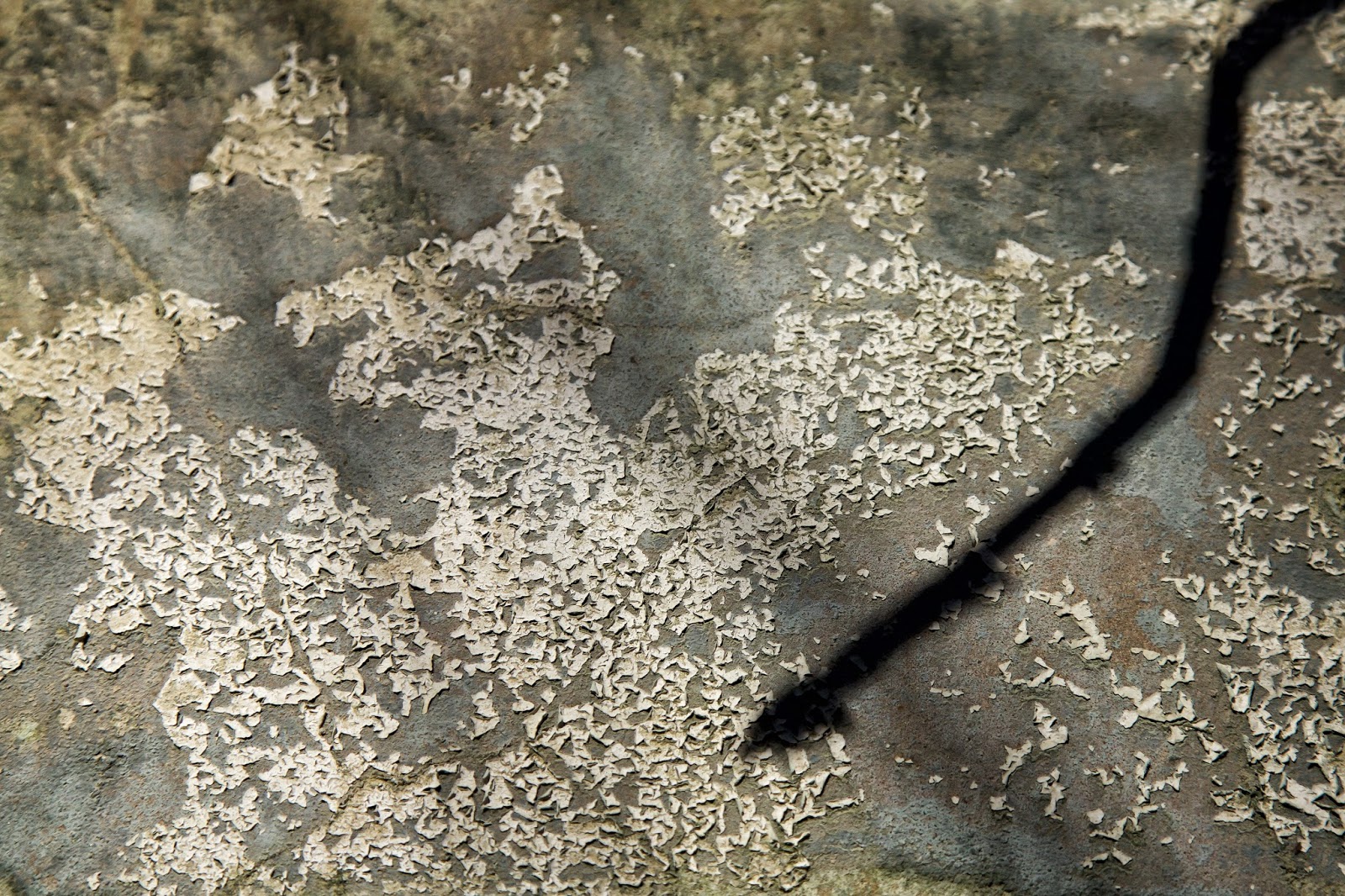

Still from Slippage (2021) – Lynda Beckett

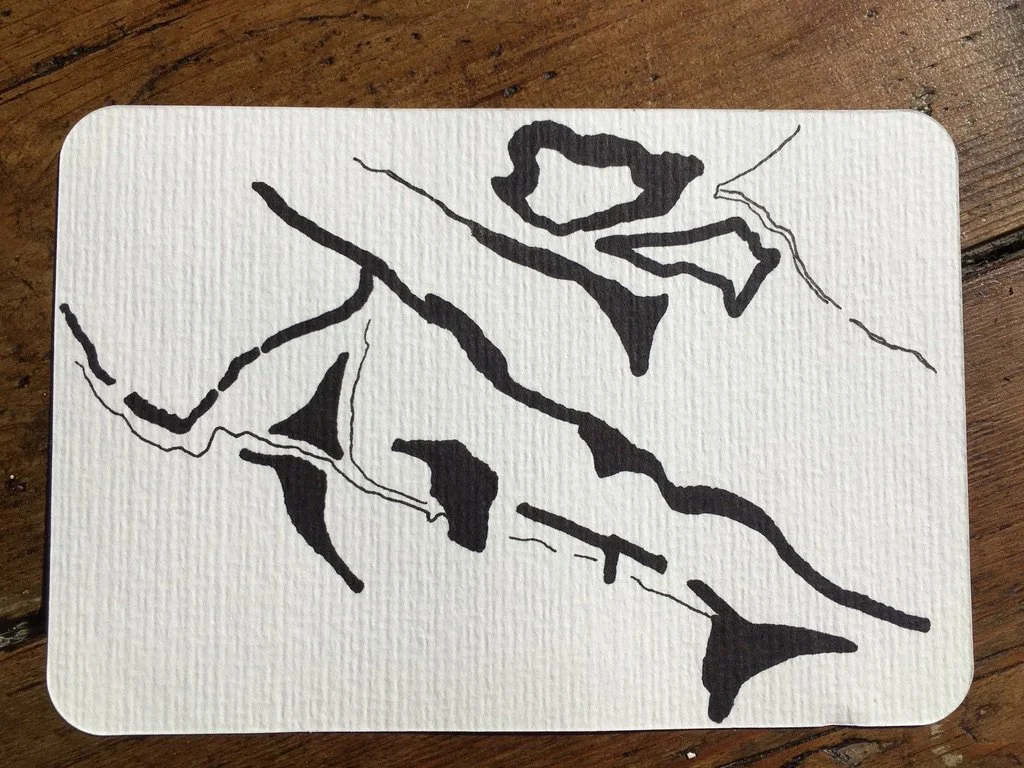

Slippage (Beckett, 2021d) and Moor Slippage (Beckett, 2021e)[3] materialised between folds and became knotworks. I gathered material as part of my making process. It revealed different virtual spaces, as my apparatus became a fluid space, a portal and a knotwork. Found data as material, folded between physical and virtual environments as my computer became another apparatus within the process of making. According to Barad, the apparatus is the matter that forms the material conditions of possibility and impossibility (Barad, 2007, p. 148). During the editing the footage slipped and the pixels multiplied beyond my control. Within this data-driven apparatus, virtual sensual spaces were revealed at the touch of a button.

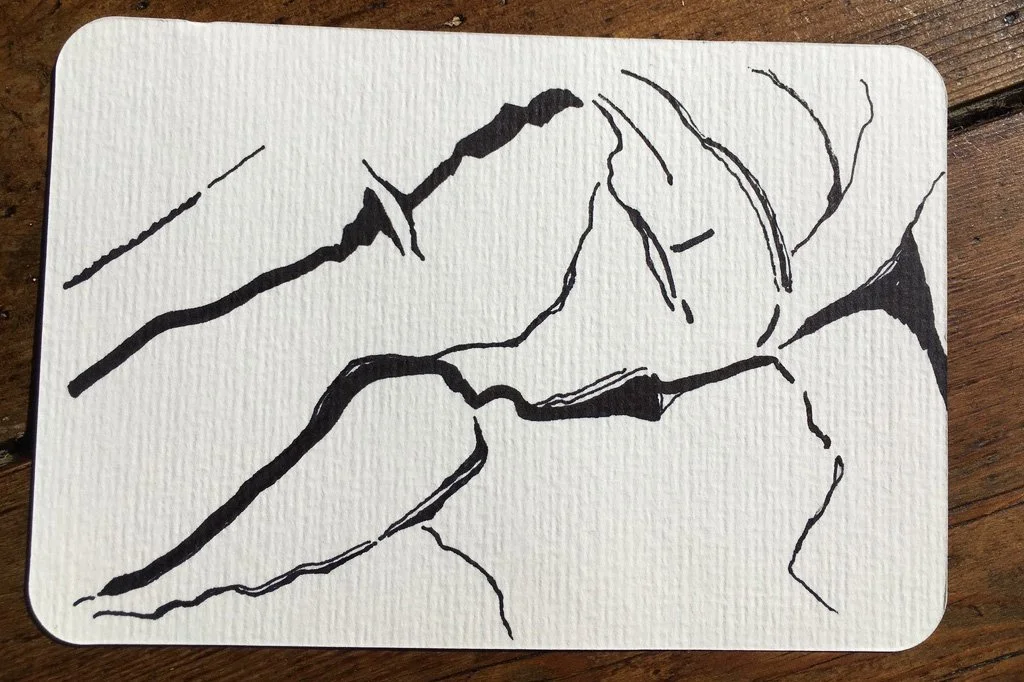

Still from Moor Slippage (2021) – Lynda Beckett

I intend to explore the matter of material within the traits of the fold as sensual, conceptual and socio-political knots, within my apparatus in more depth during the next stage of my research[4]. However, before unravelling the threads of my zoe/geo/techno assemblage in the form of the knot, I will briefly explore how the knot is perceived as an entity in history and art practice.

[1] See 31/10/2012-21, (Beckett, 2021c) - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_8hfHCY3POk

[2] Initially, ‘The paradigm’ seems to relate to a framework, a cartography, the physical surface, structure of the form or space. Yet, ‘this formal element appears only within infinity, in what is incommensurable and in excess’ Deleuze (2006, p. 43).

[3] See https://www.lyndabeckett.org/#/slippage/ and https://www.lyndabeckett.org/#/moor-slippage/

[4] Other PhD-level research that draws upon folds and ‘The Fold’ (Deleuze, 1991) includes, Tsai-Chun Huang's, In-Between Pleats (2020) and Sophie Bouvier Ausländer’s, On tangibility, contemporary reliefs, and continuous dimensions (2019).