Subjectivity and Feminisms Research Group at Chelsea School of Art

Space for Risk: Performing Feminisms

March 2025

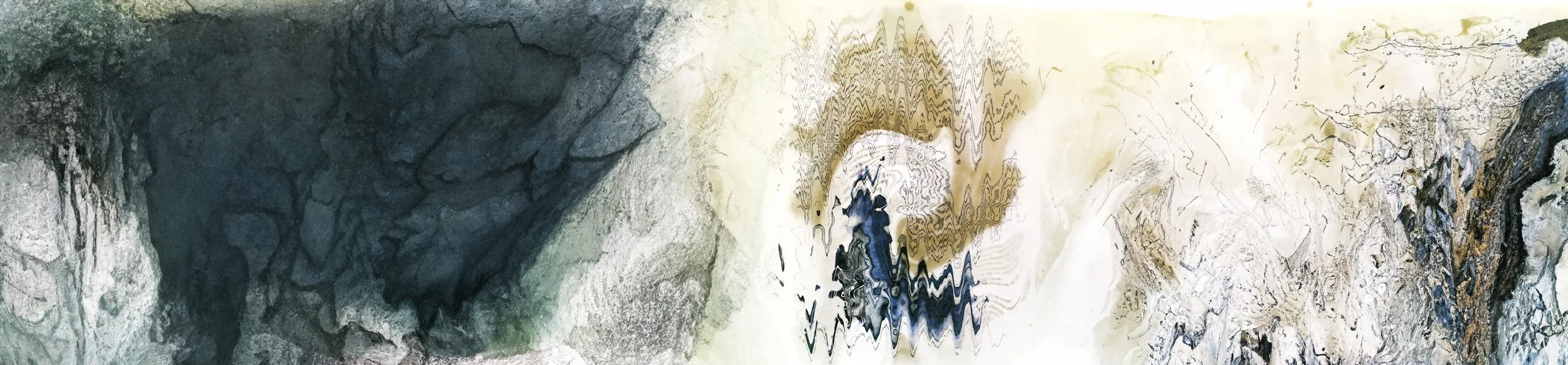

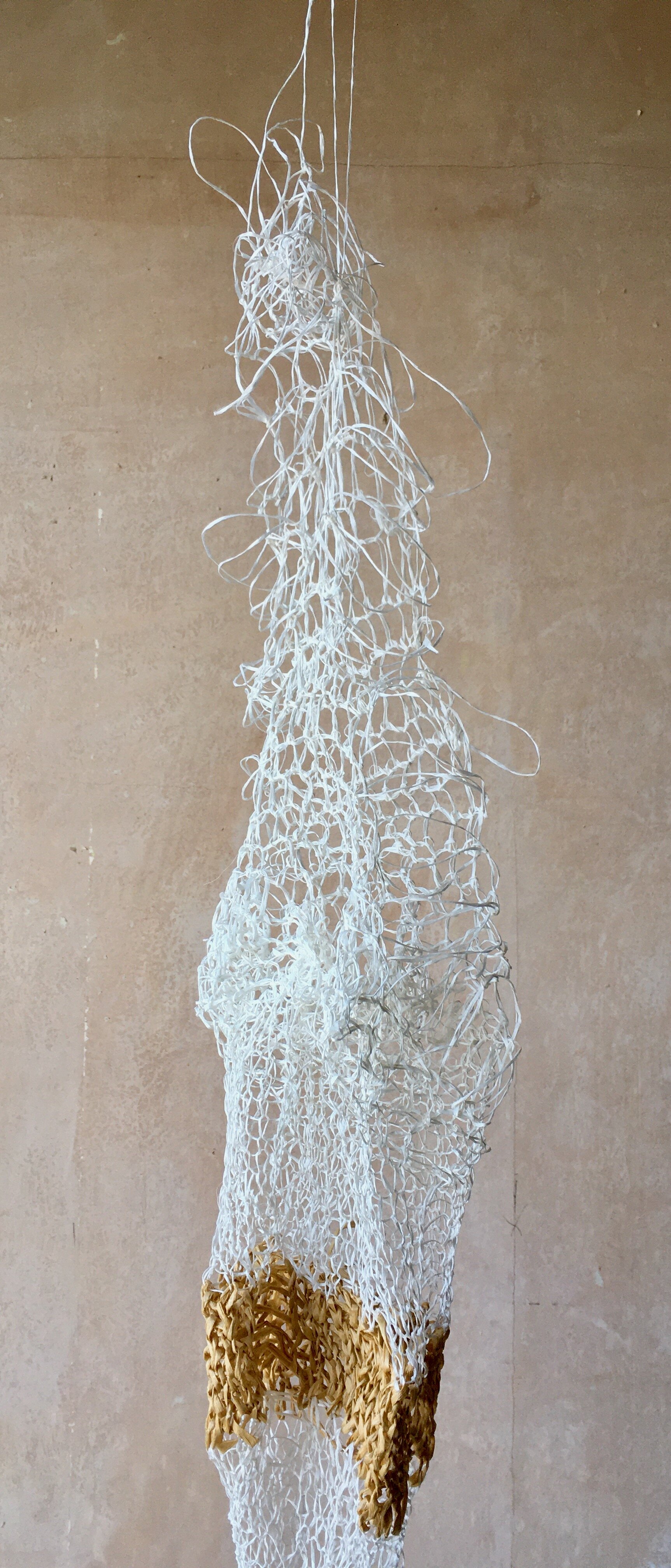

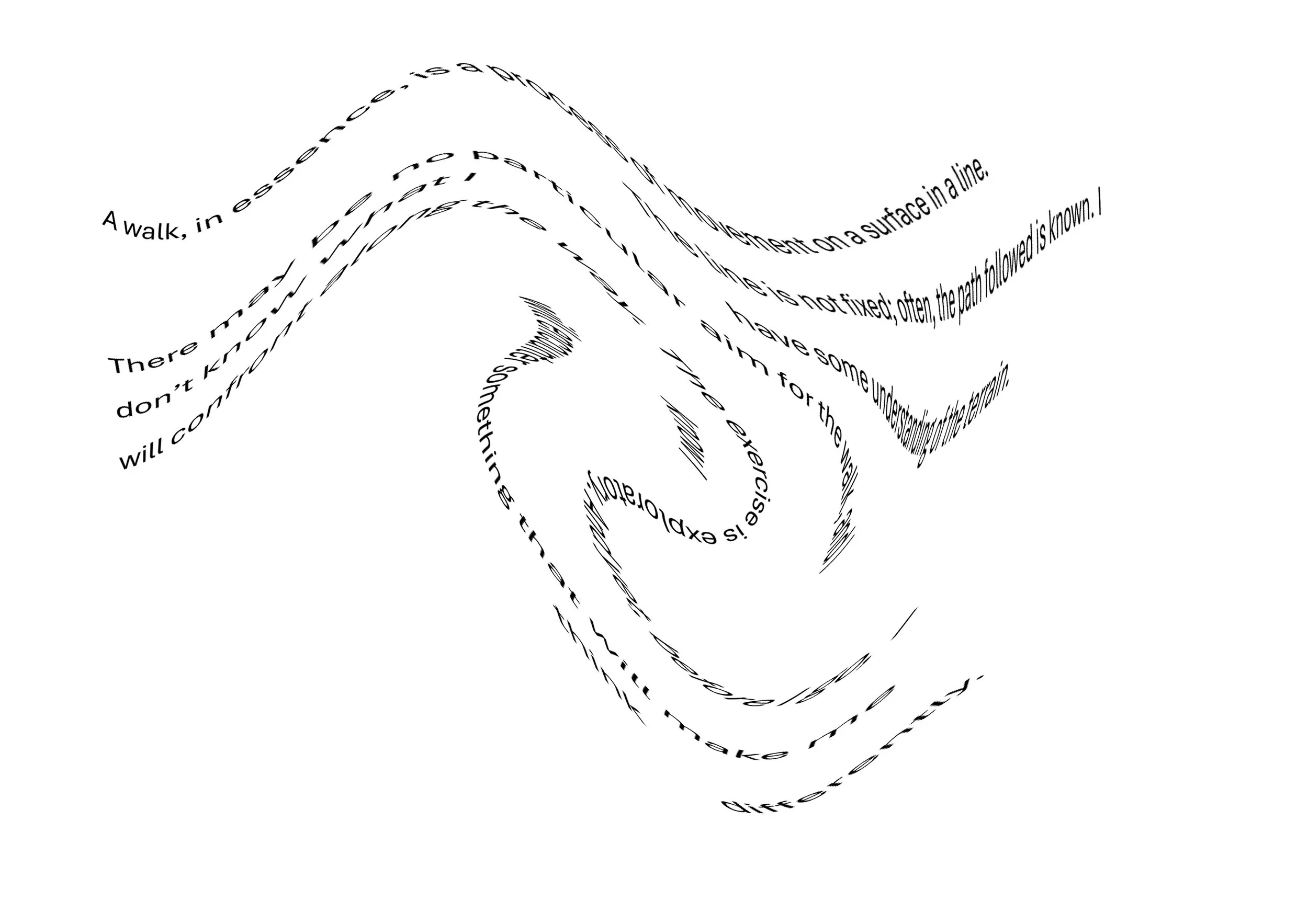

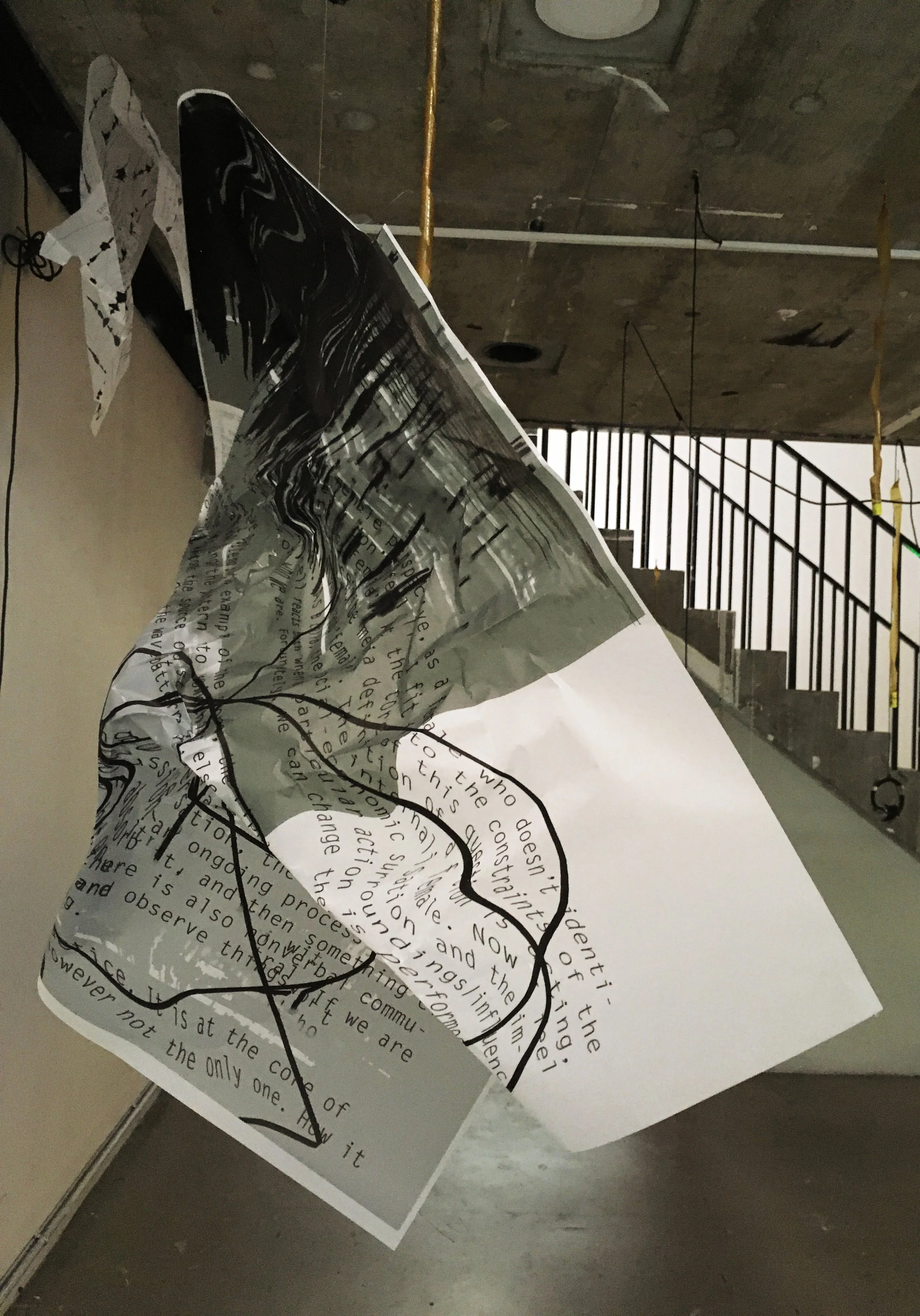

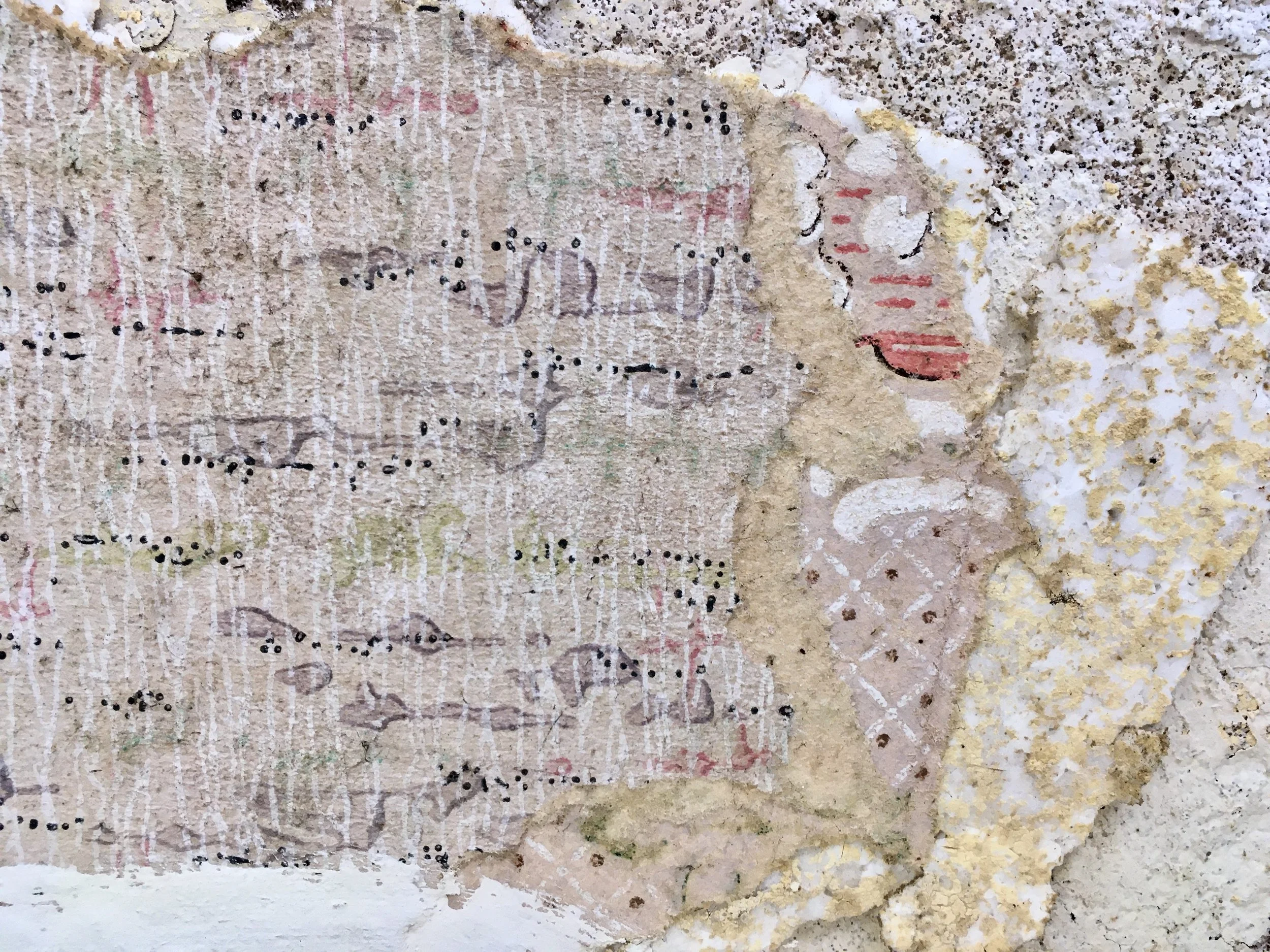

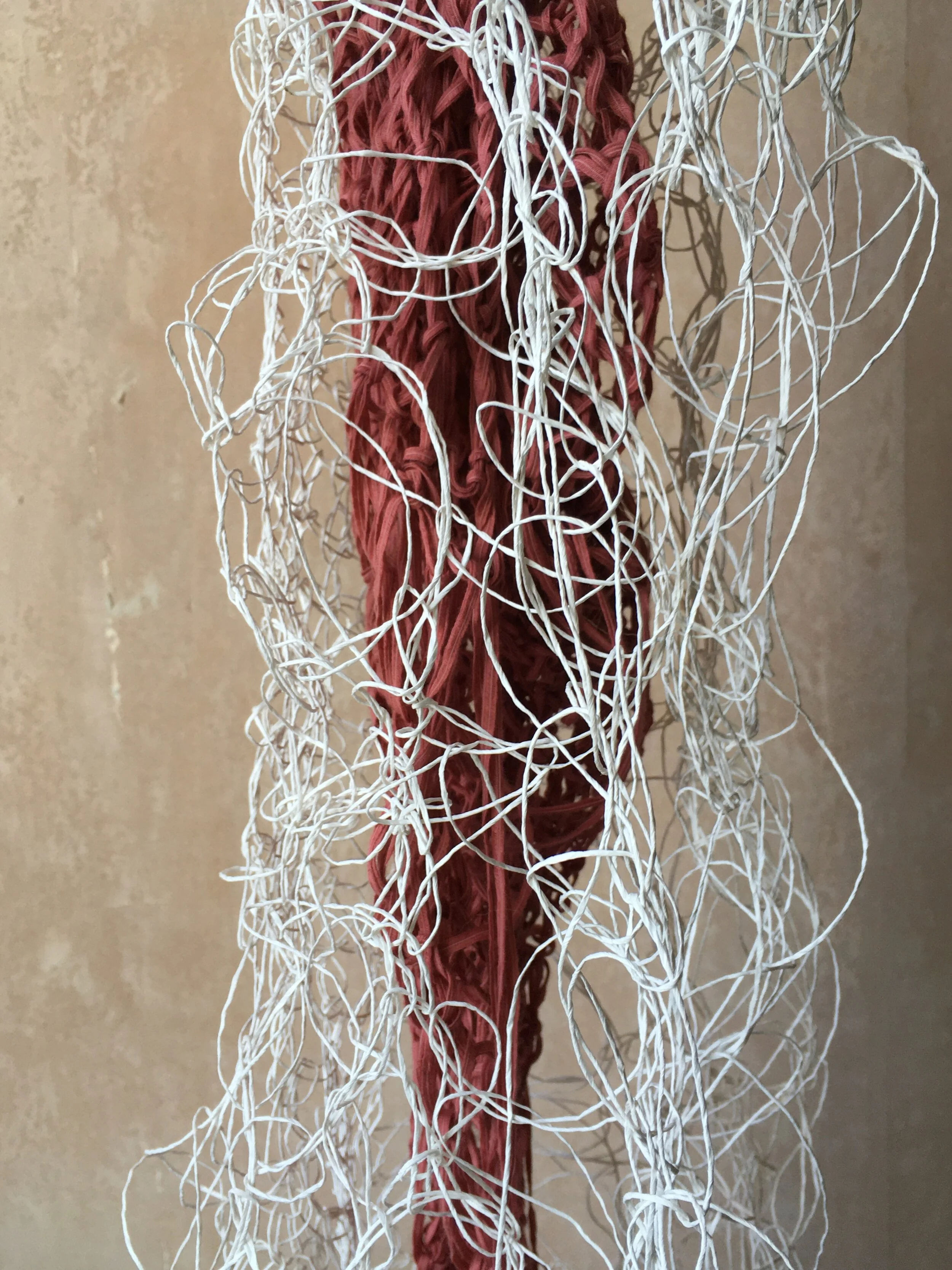

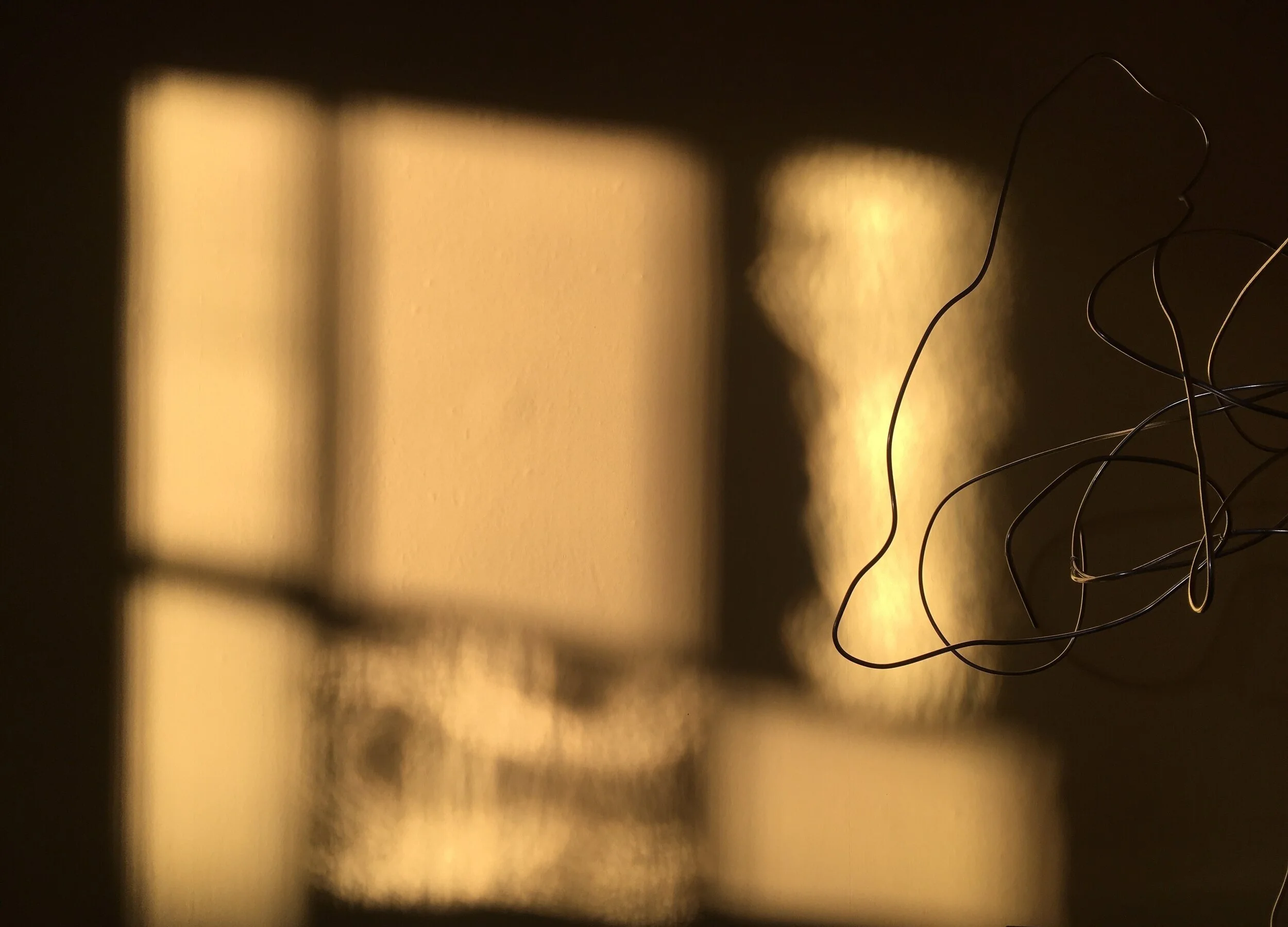

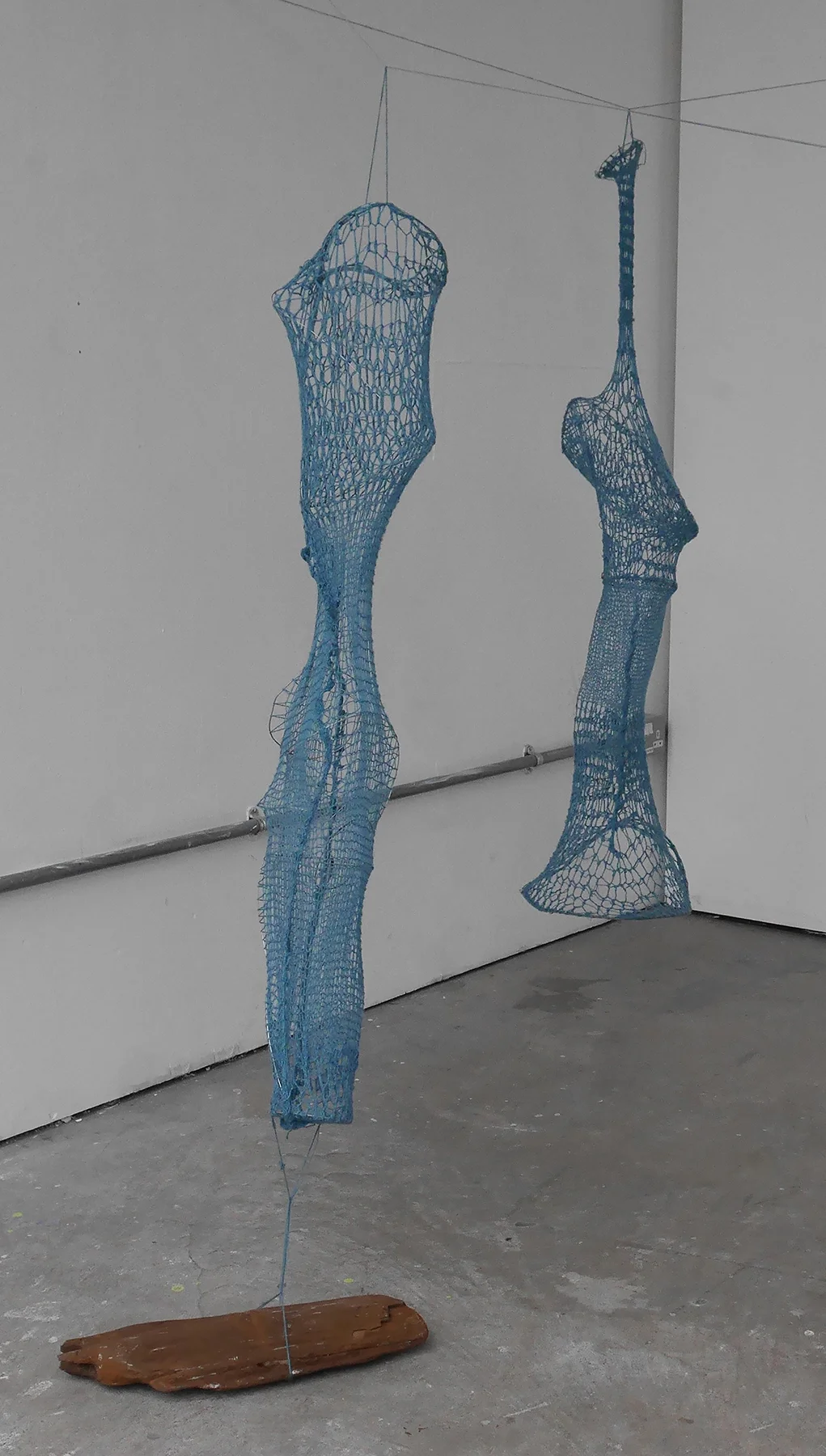

Last night, for only the third time, I stepped into performance as part of my research-creation. I wandered into a space that was open to risk. A place that felt like an opening, an unfolding, and a moment to breathe. The air was filled with the unknown, and yet there was a sense of care. Held within the Subjectivity and Feminisms Research Group at Chelsea School of Art, Space for Risk: Performing Feminisms (2025) was an event within an event, a space of becomings where the many threads of being, becoming animal and woman could weave together, and unravel through dialogue, presence, and performance.

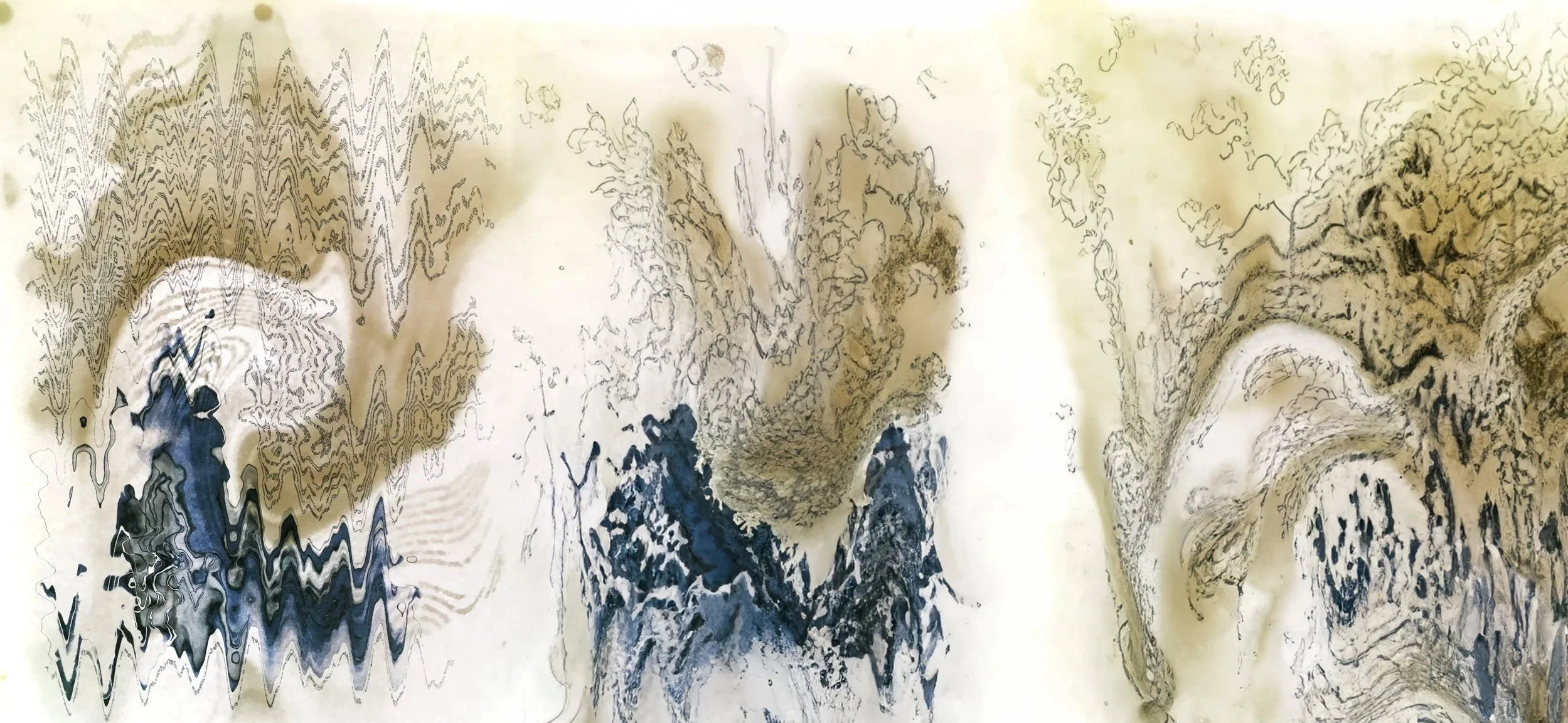

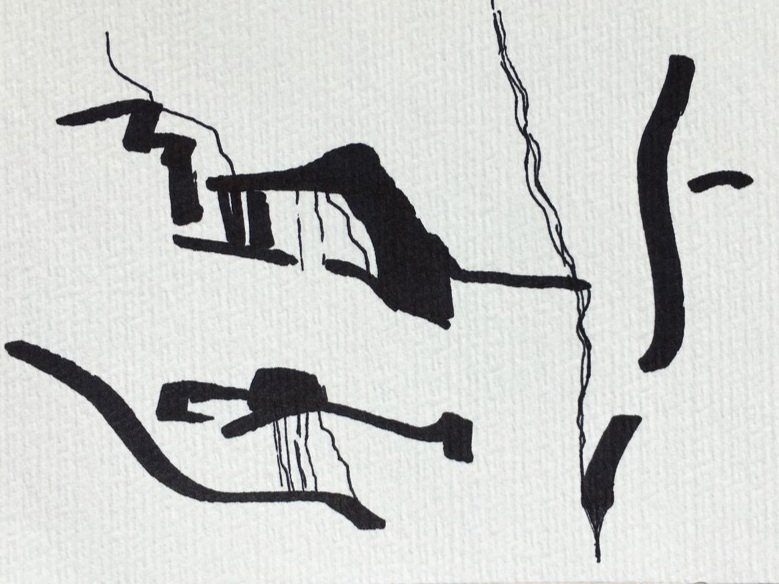

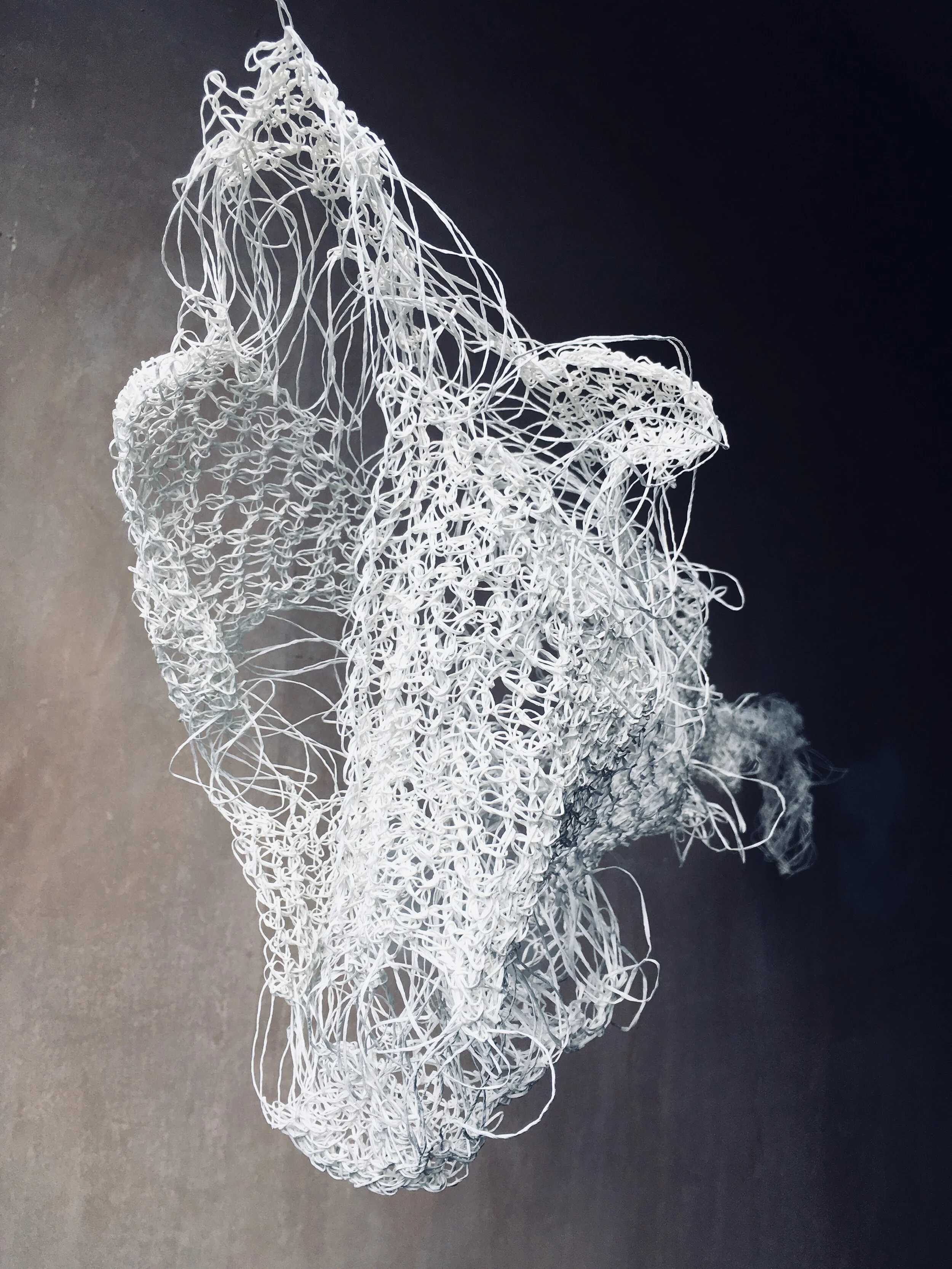

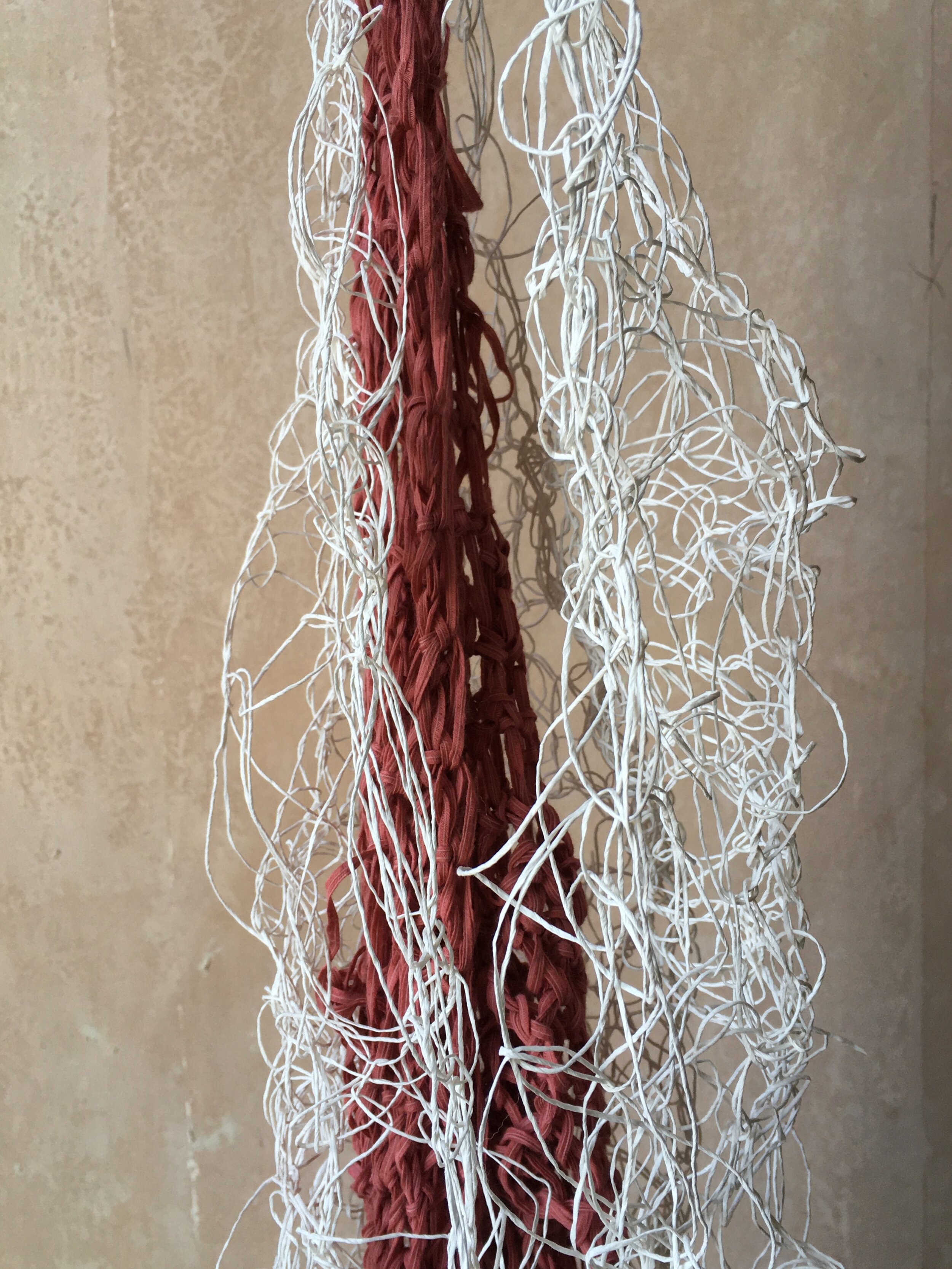

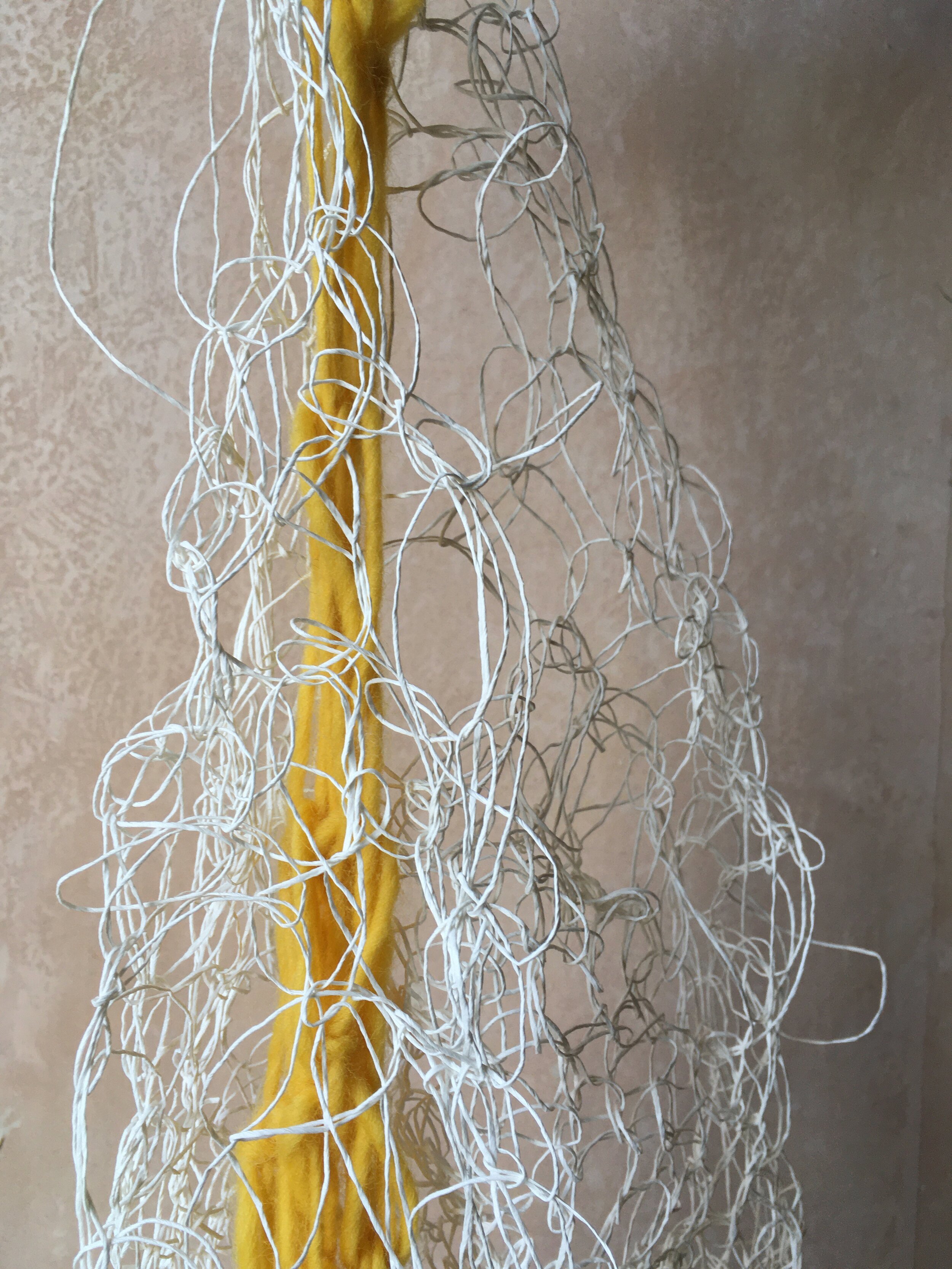

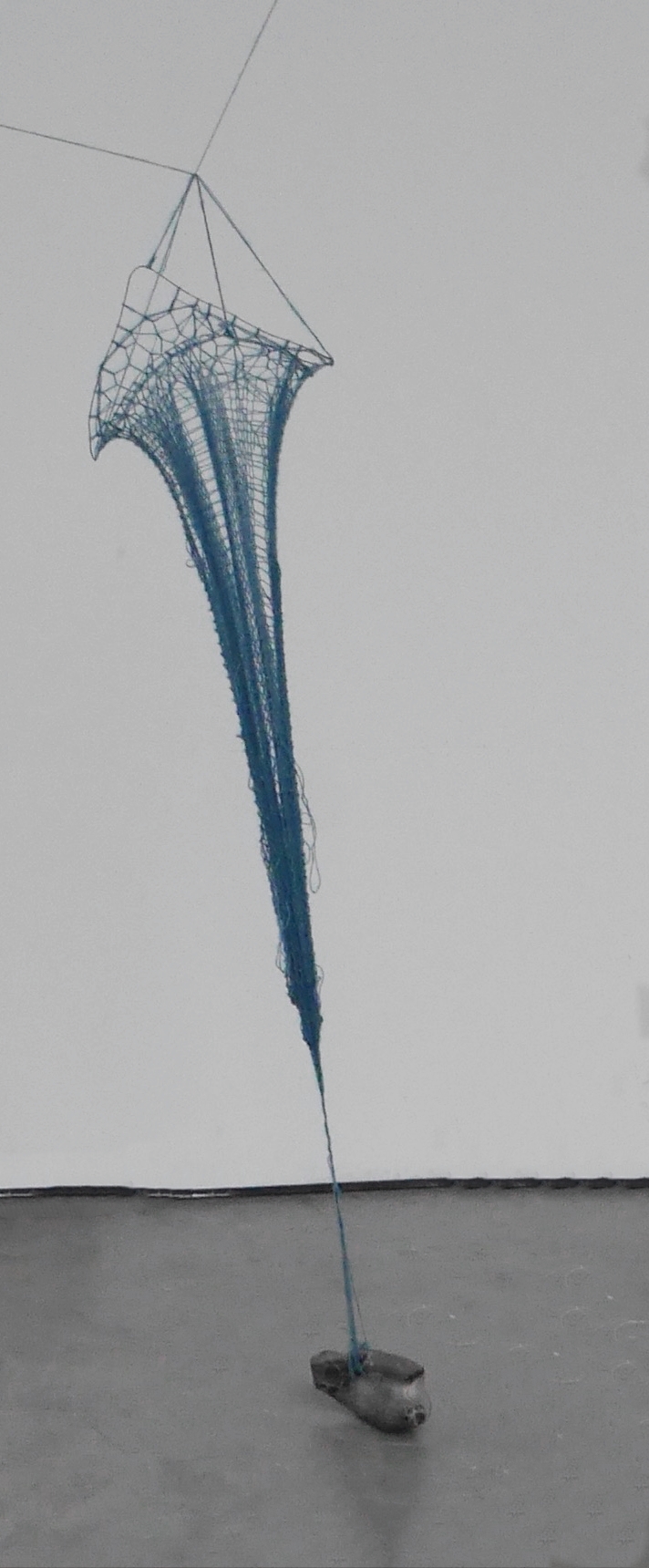

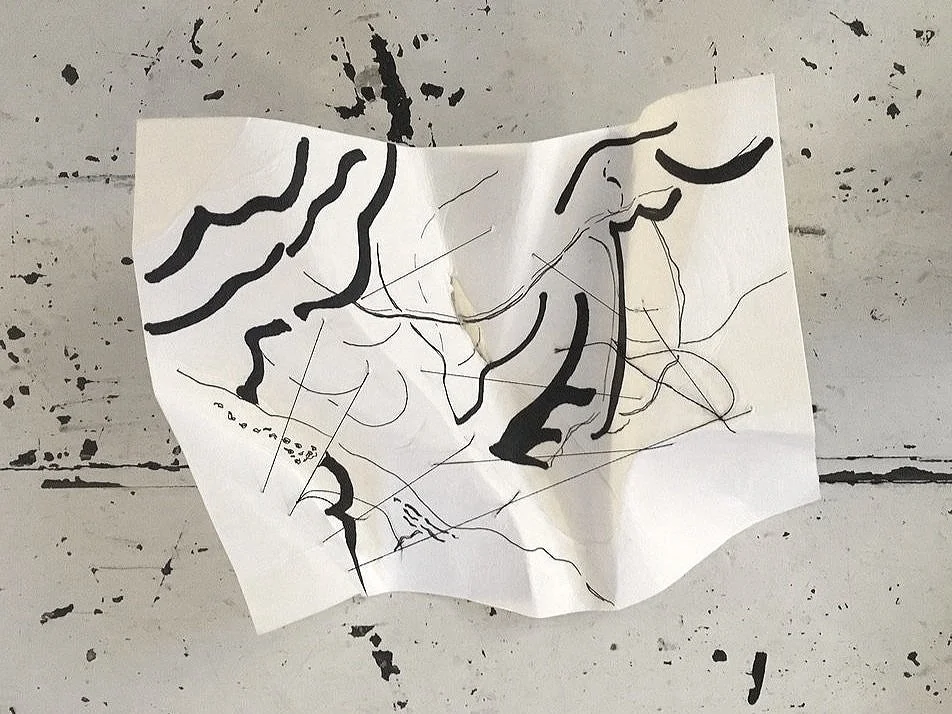

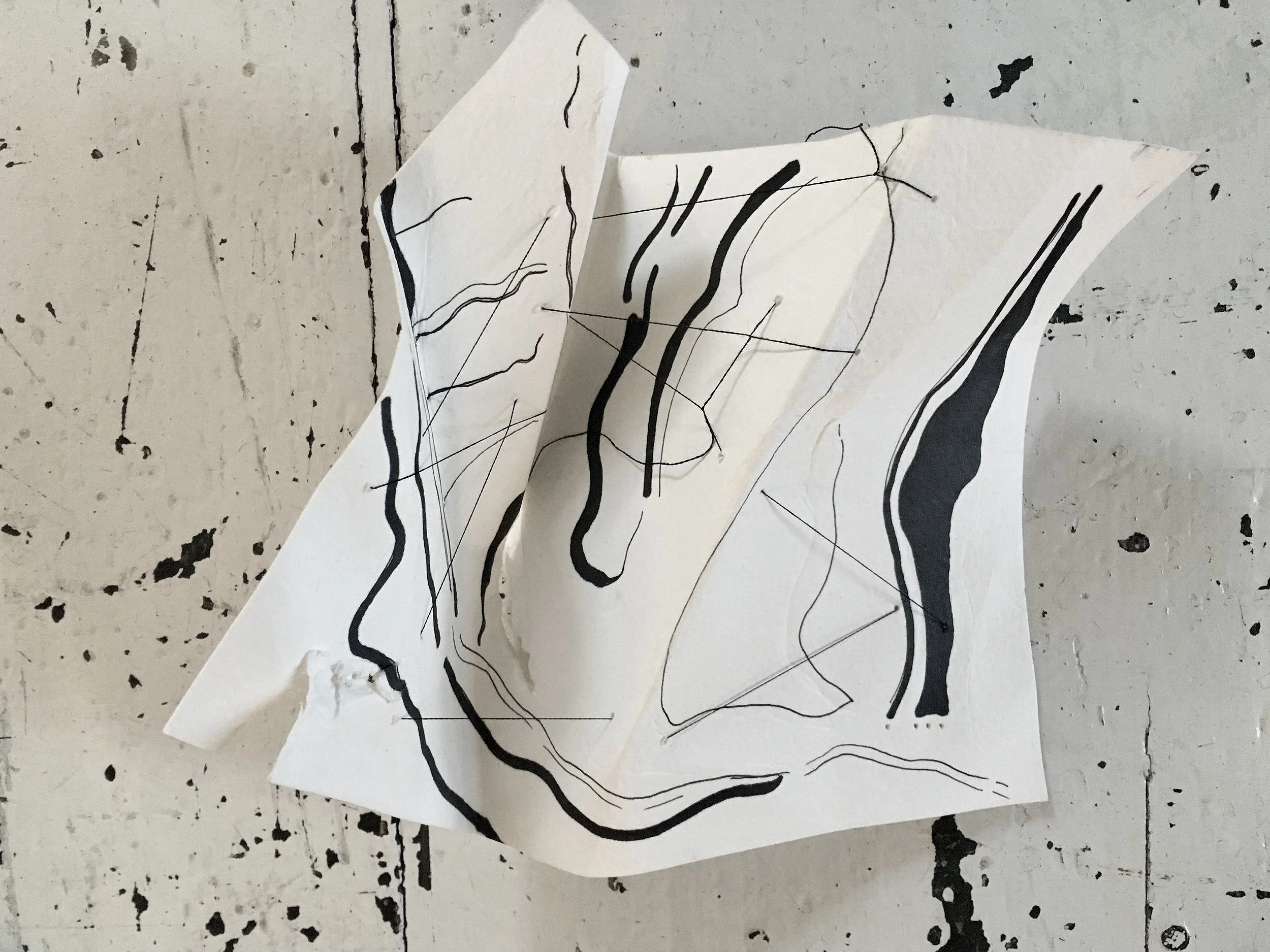

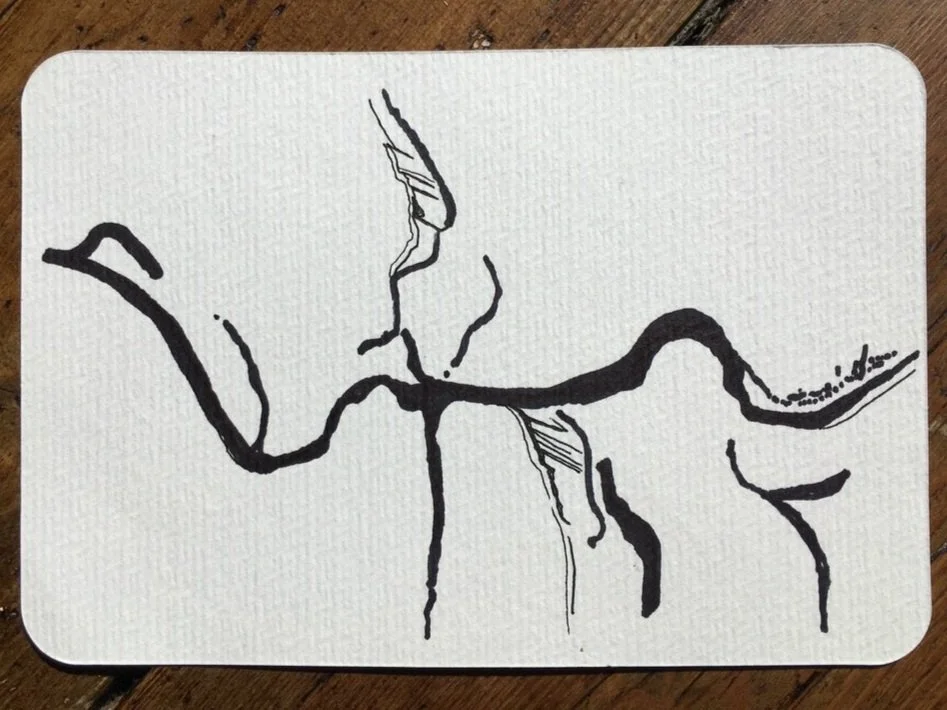

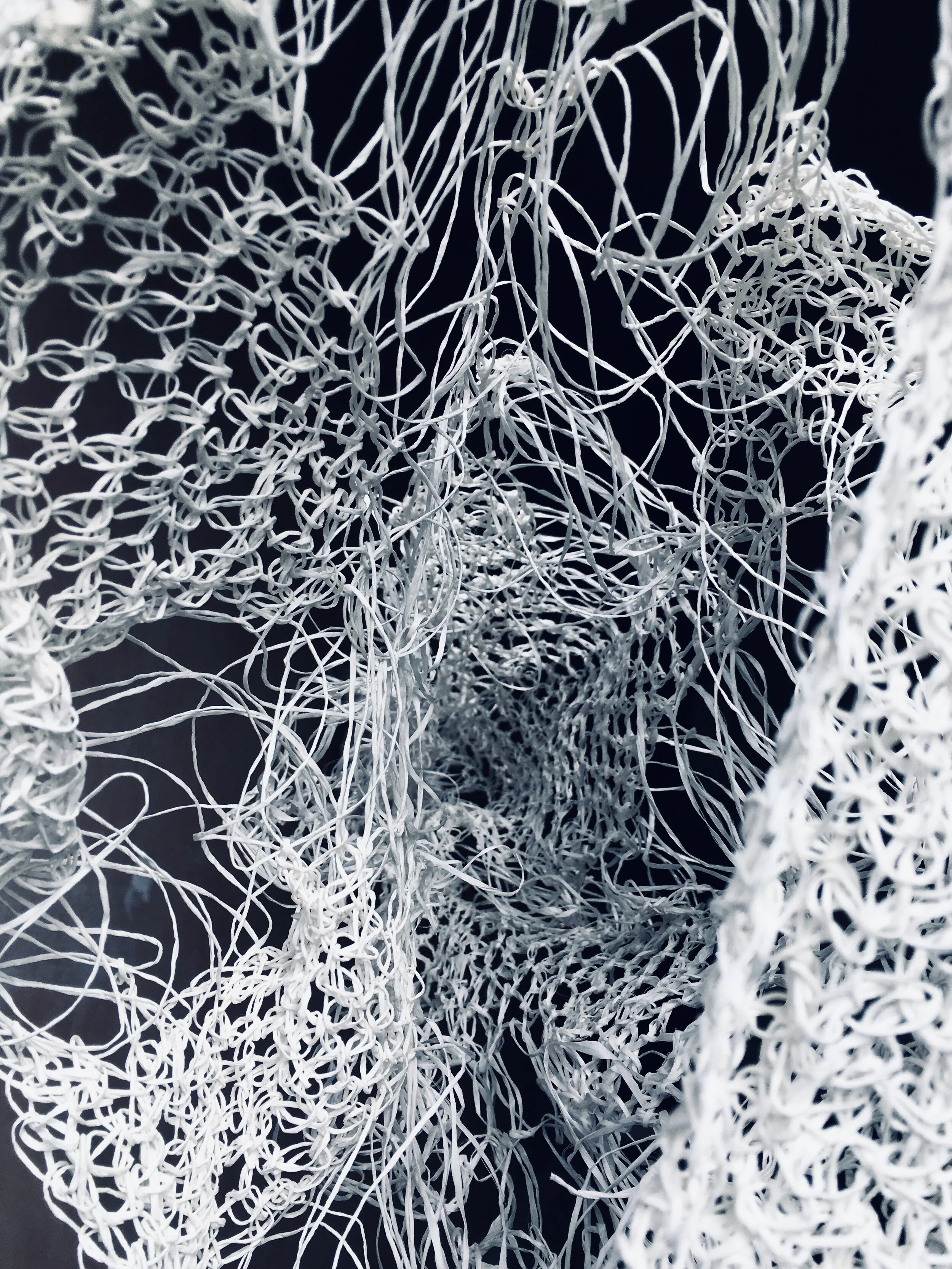

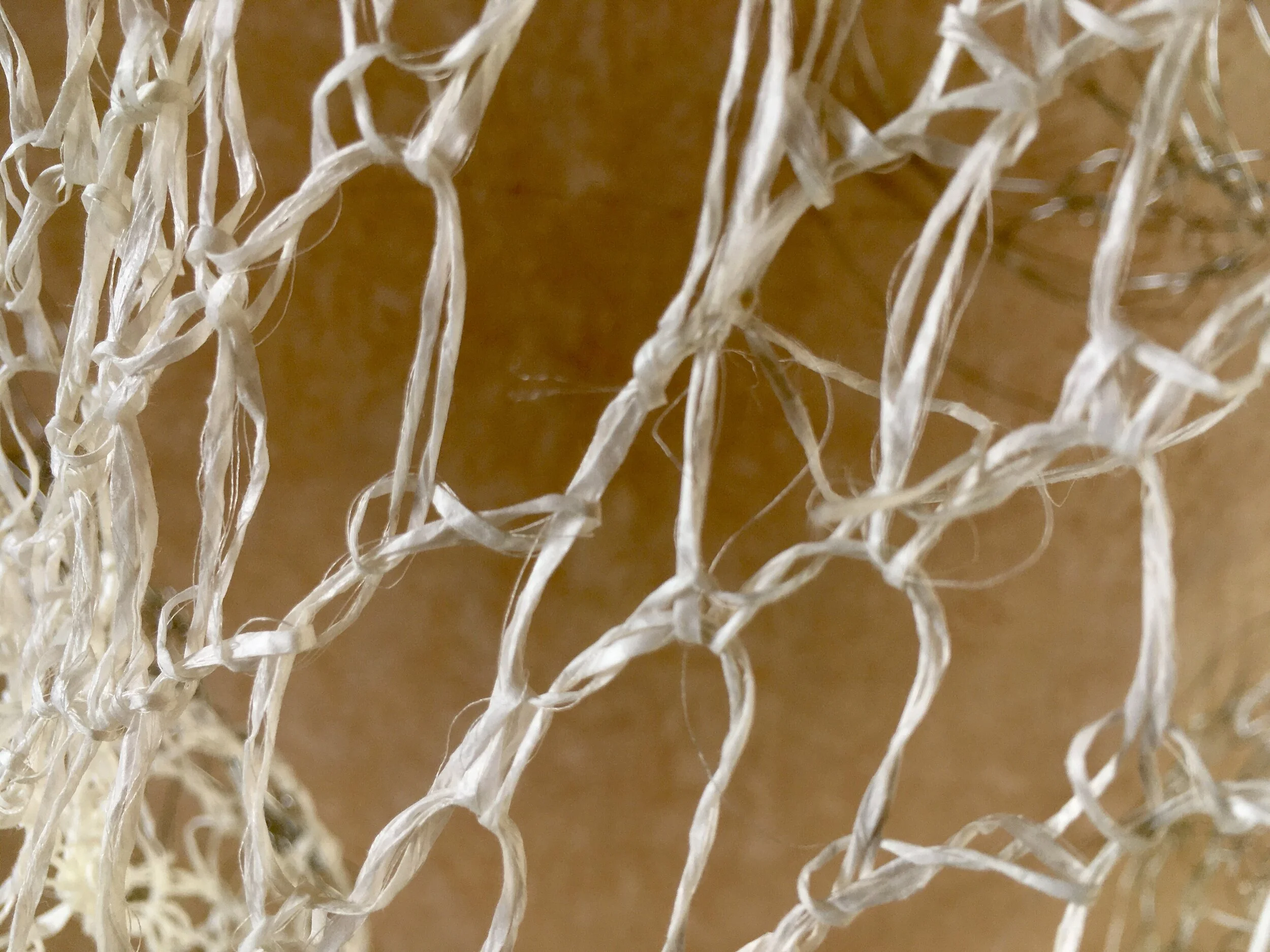

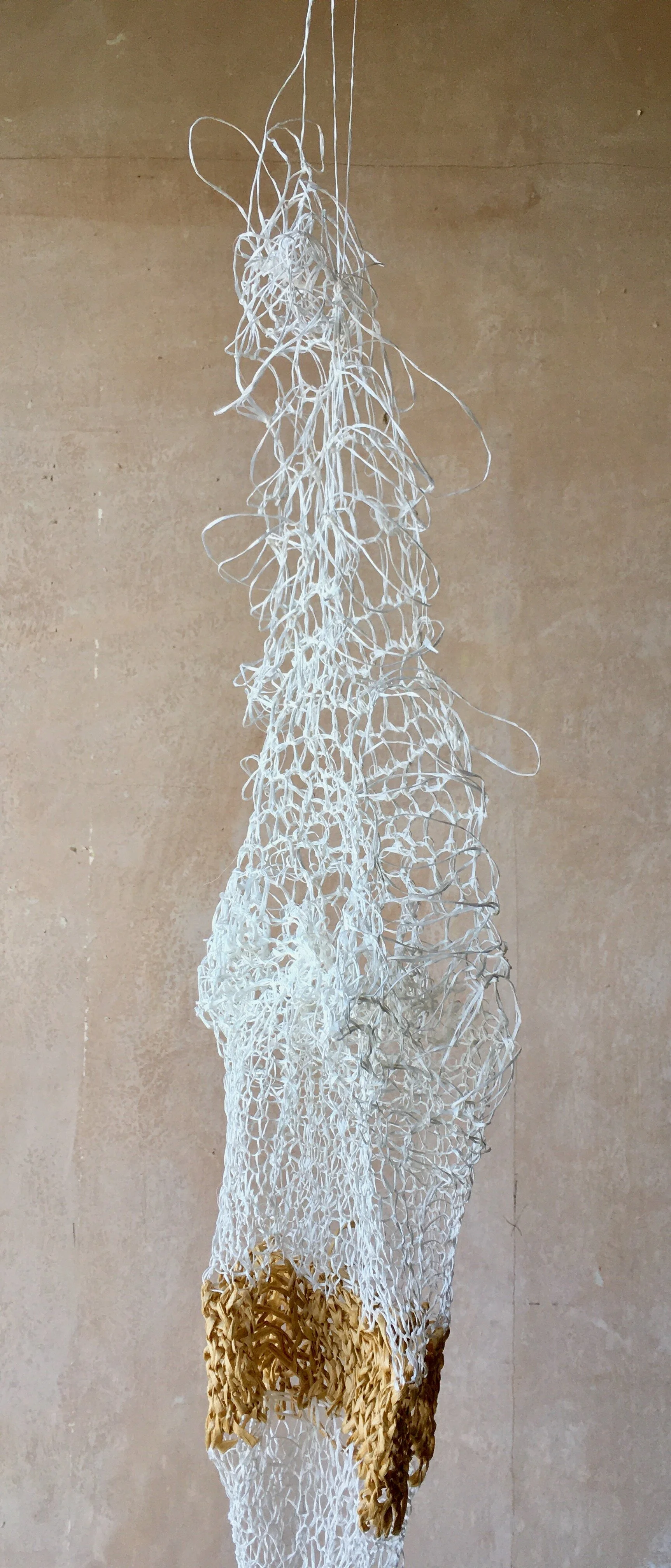

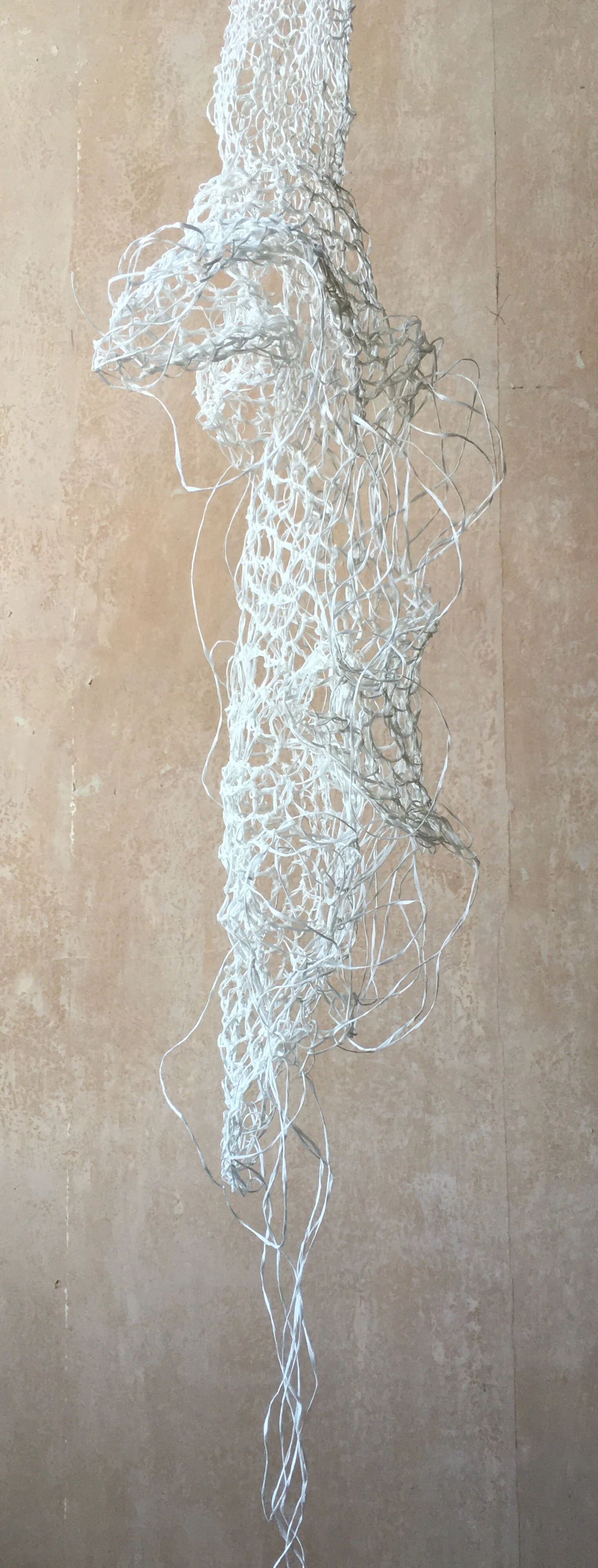

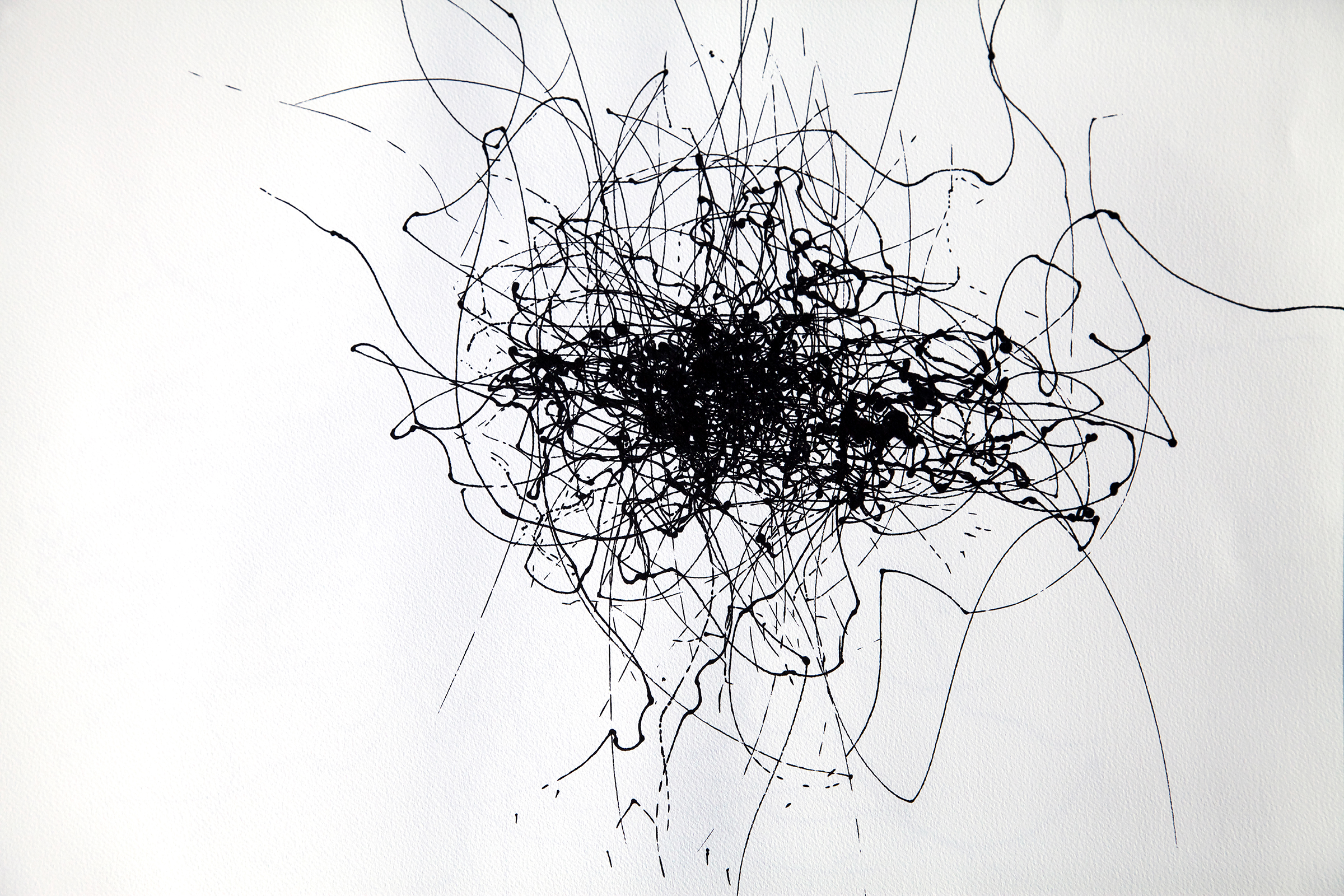

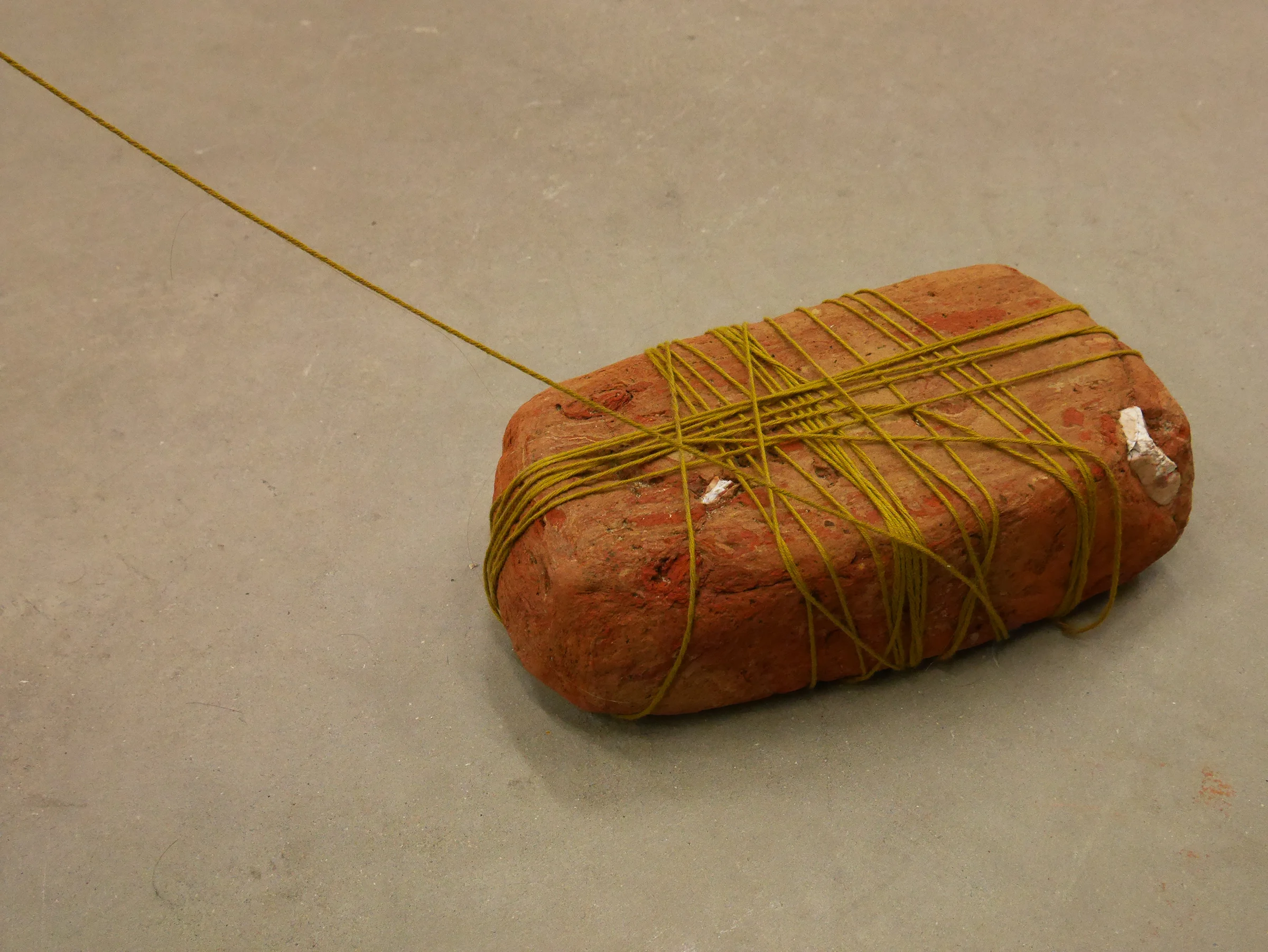

What I write here, in the form of written language, has only been made possible through the event itself, which in turn has propelled the concept of knotwork forward through research-creation. By this, I mean that the process of doing – the impromptu making of physical work, a performance, among others – has moved the form of knotwork beyond a purely philosophical proposition. The performance was a knot within an event, a knotwork, which developed into a living concept. The formation of knotworks within my research-creation practice continues to be intuitive and somewhat chaotic in its realisation within space.

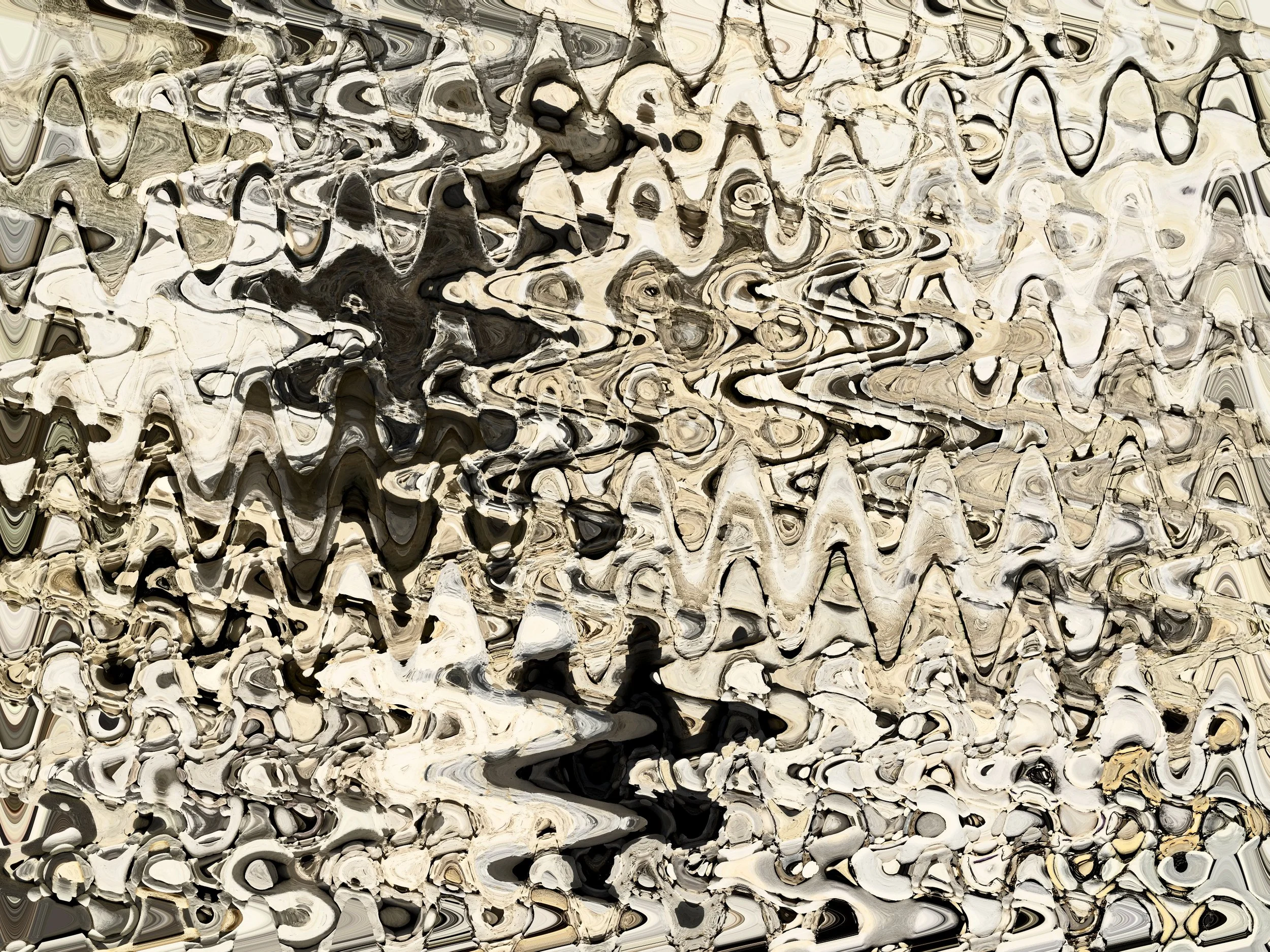

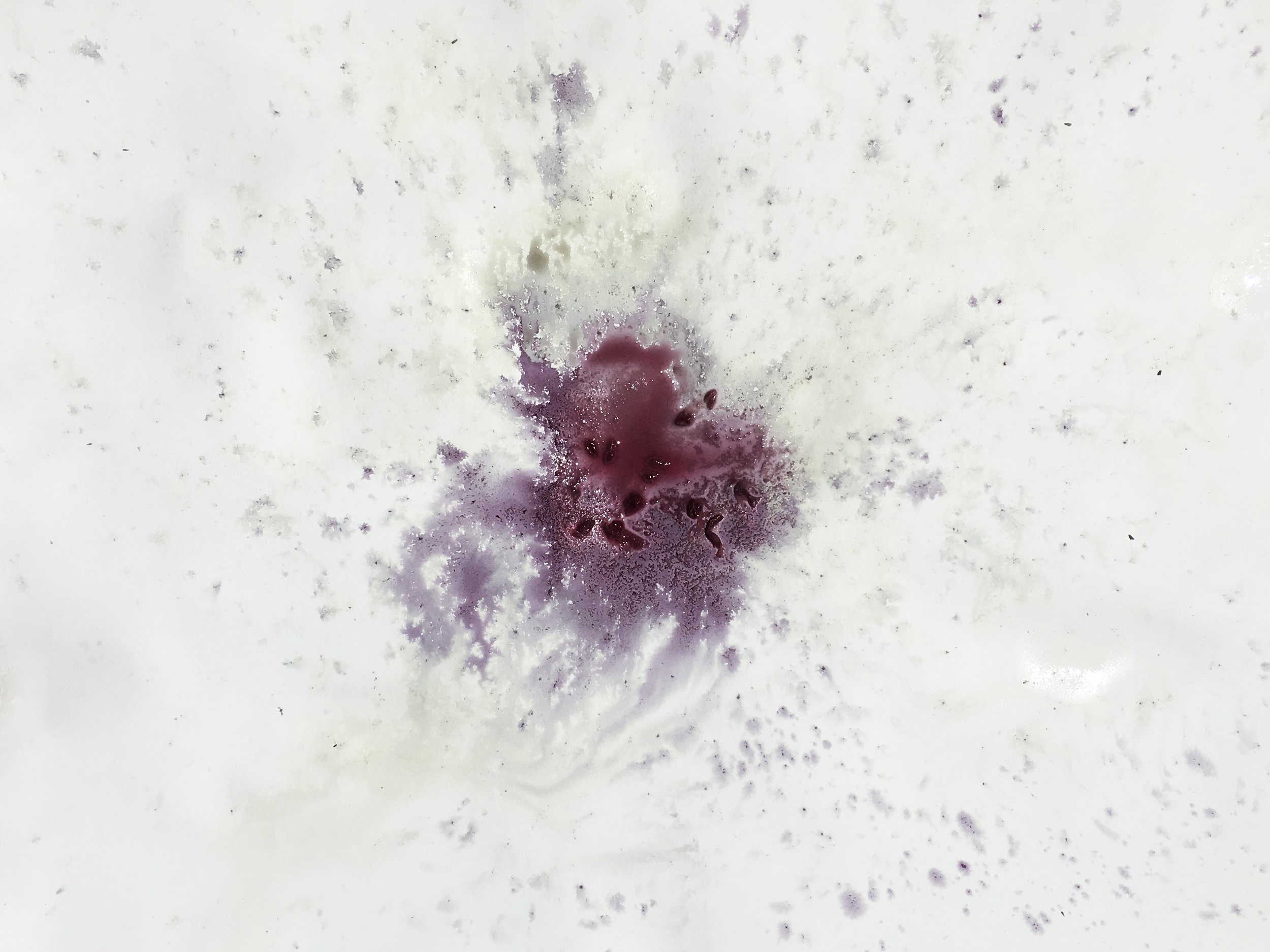

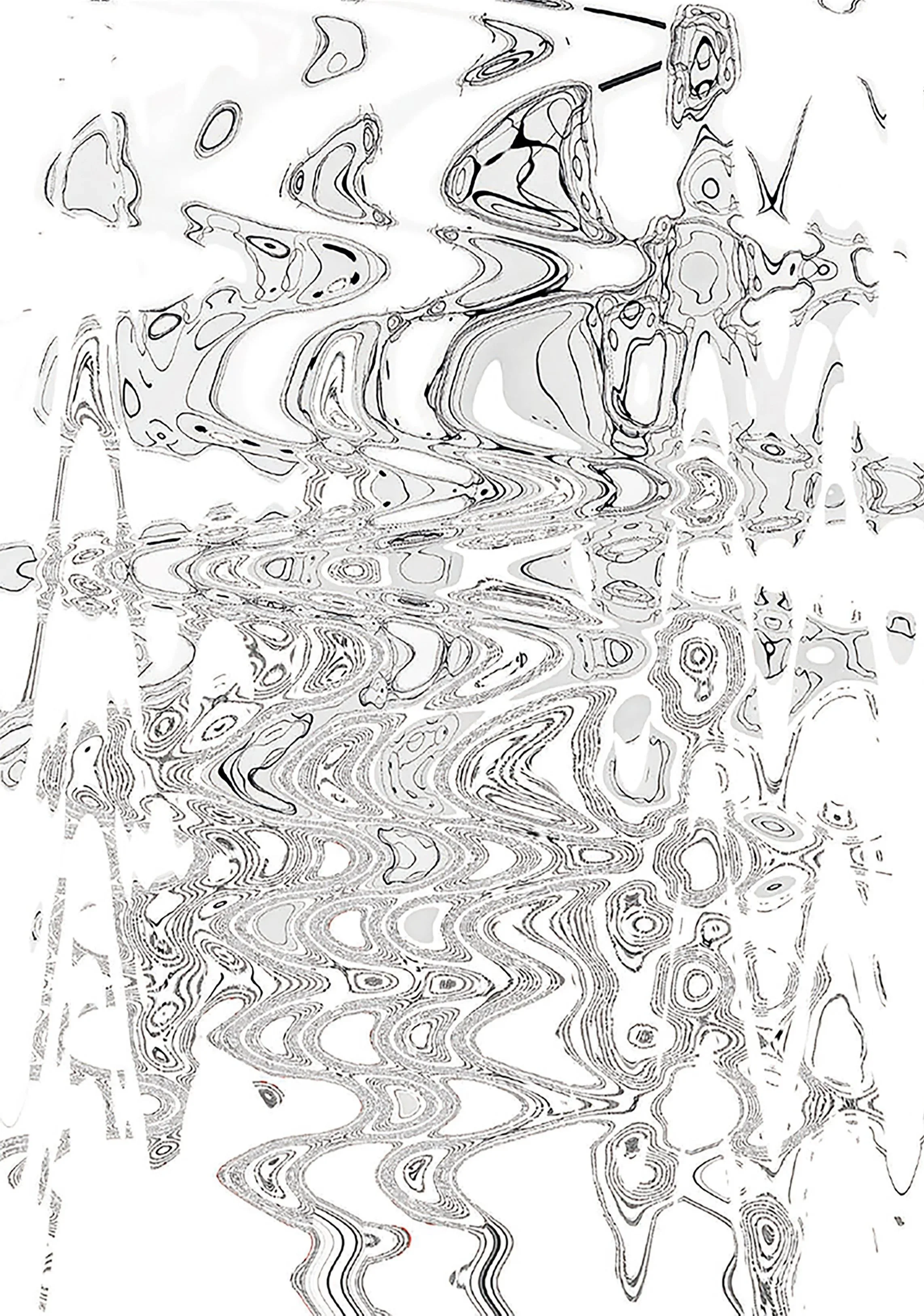

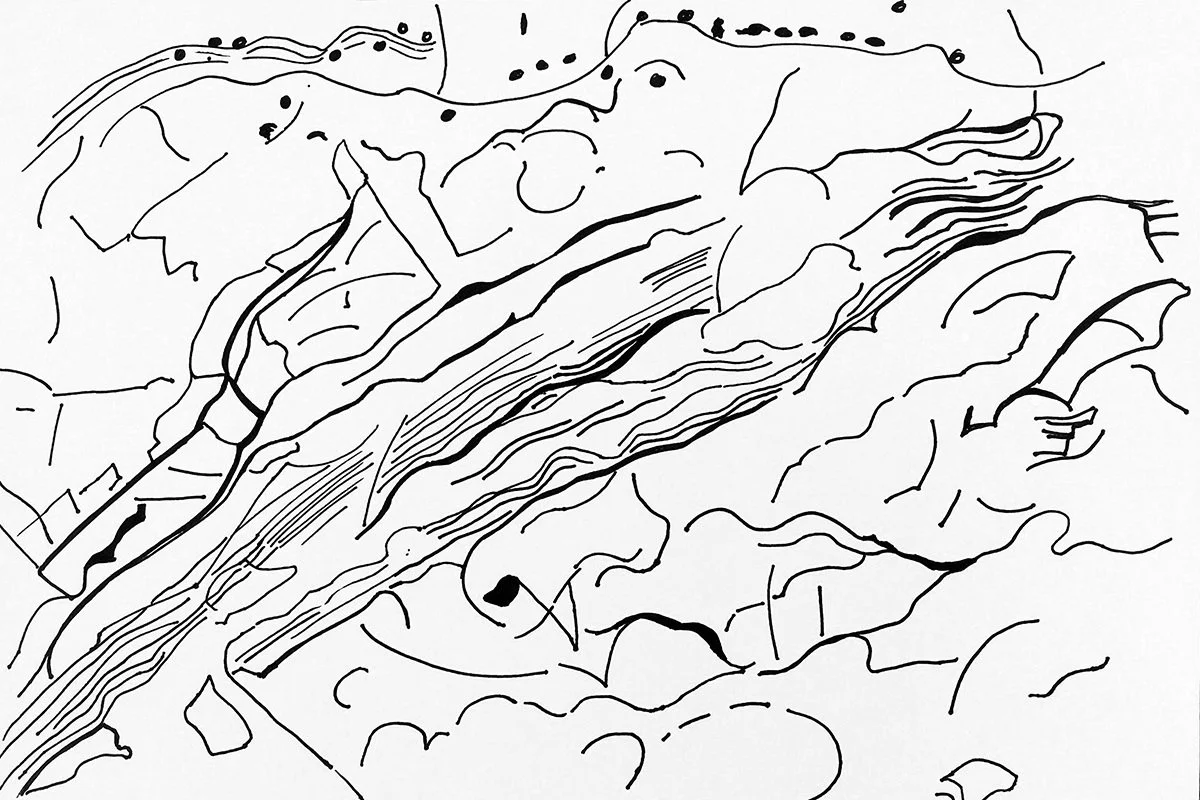

Within duration, as Henri Bergson would conceive it, the development of the concept of knotwork has enabled what Elizabeth Grosz might describe as an intensity of affects and percepts: a visceral response that demands to be performed (2008, p. 27). Grosz further explains that such events, where a certain amount of chaos – or perhaps the unknown – is allowed to sit within the brain, occur when ‘we throw over chaos in order to extract an element, a quality, a consistency from chaos, in order to live with it’ (ibid., pp. 27–28). Moreover, Grosz continues by drawing on Deleuze and Guattari, who refer to these moments as ‘brain-becomings’, when ‘the brain is the junction – not the unity – of the three planes’ (1994, p. 208): philosophy, art, and science intertwining. It is within such a space – an entangled field where chaos is not eradicated but lived with – that that knotwork, as both method and concept, is continually formed and reformed.

According to Deleuze and Guattari, ‘to become animal is to participate in movement, to stake out the path of escape in all its positivity, to cross a threshold, to reach a continuum of intensities that are valuable only in themselves, to find a world of pure intensities, where all forms come undone, as do all significations, signifiers, and signifieds, to the benefit of an unformed matter of deterritorialised flux, of nonsignifying signs’. (Deleuze and Guattari, 2008, p. 13).

During my performance, I had no intention to ‘stake out a path of escape’ (ibid., p. 13). Without knowing, I found myself within a space where I was free to become animal, to become woman without inhibition.

This articulation of becoming-animal resonates profoundly with my concept of knotwork within research-creation. Knotwork, like becoming, does not adhere to fixed forms or stable meanings; rather, it is composed of thresholds, crossings, and intensities that continually reconfigure themselves. Within knotwork, forms come undone, threads are folded and refolded, and signification is deferred, generating a living, deterritorialised field of relations. It is not the representation of movement, but movement itself: an unformed matter of flux where artistic, conceptual, and material forces intersect and transform. In this sense, knotwork operates as a topology of pure becoming, a dynamic weaving-together of nonsignifying signs, where risk, transformation, and emergence are sustained within the very fabric of practice.

Friedrich Nietzsche states:

Art reminds us of states of animal vigor; it is, on the one hand, an excess and overflow of blooming physicality into the world of images and desires; on the other, an excitation of the animal functions through the images and desires of an intensified life—an enhancement of the feeling of life, a stimulant to it. (Nietzsche, 1968, p. 422)

Nietzsche’s emphasis on ‘animal vigor’ reinforces Deleuze and Guattari’s account of becoming-animal. Both affirm movement, excess, and the overflowing of form as vital processes. Nietzsche describes art as the manifestation of intensified life, where physicality spills beyond its ordinary boundaries into states of excitation and sensation. Similarly, Deleuze and Guattari’s notion of becoming-animal speaks to the dissolution of fixed forms and the inhabitation of pure intensities.

Such spaces for ‘states of animal vigor’ are rare, yet I would argue they are essential for exploratory research within the UAL community. I wonder why it has taken me so long to discover this group—a space where many powerful readings and performances freely materialised in one evening. A space of intensity, where method and embodiment, risk and uncertainty, coalesced into something visceral, something sensual that vibrates with life.

Reflecting on this, I find an echo in Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of ‘becoming-animal’ (1987, p. 275) and ‘becoming-woman’ (ibid., p. 276), both understood as processes of deterritorialisation that move beyond fixed identities, opening new potentials for thought, movement, and expression. The performance space at Chelsea enabled precisely that: an undoing of stable forms, a movement towards the thresholds of identity where bodies, gestures, and voices wove into an assemblage of becomings. If Nietzsche’s ‘animal vigor’ speaks of an overflow of life into sensation, then Deleuze and Guattari’s becoming reveals how this excess unbinds the subject from categorical fixity, allowing a continuous flow of transformation.